The city of Kherson, on the banks of the Dnipro River in southern Ukraine, was taken by Russian forces without much fight in early March, days after the invasion started.

It remains Russia‘s biggest victory in the war and still one of the only major cities that its forces have managed to capture.

In recent weeks, however, Ukrainian forces have struck three key bridges over the river, making them virtually impassable for heavy vehicles – the aim being to slowly strangle Russian supply lines and cut off thousands of soldiers in the city.

Ukraine ‘kills 200 Russians in a day’ – war latest

A full-on Ukrainian counteroffensive is thought to be imminent.

Making contact with anyone still trapped in Kherson is hard – most people are understandably either too frightened to take the risk, or simply do not have a phone or internet connection with the outside world.

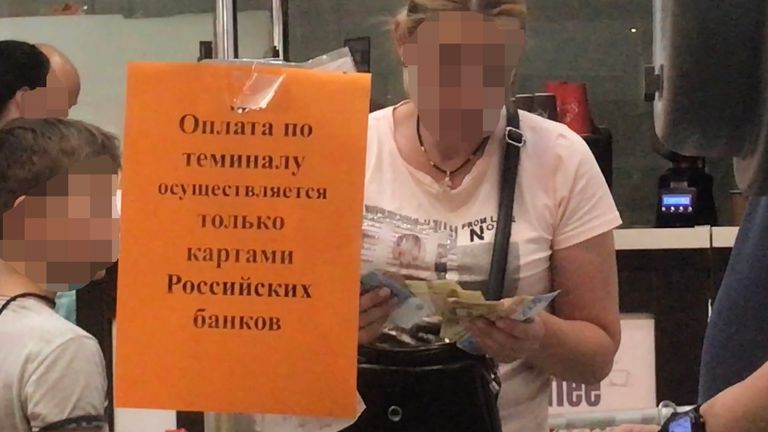

Ukrainian mobile phone networks have been shut down and replaced with insecure Russian equivalents that are bugged and do not allow international calls.

Websites such as Google, Instagram and YouTube are blocked and access to international news is almost impossible.

There is one small area in the city, known to a few people, that still connects with Ukrainian phone networks – people go there to send and receive messages when they can.

In the villages outside Kherson city, people climb on to roofs in search of phone signal. Meeting friends or family takes planning and courage.

“We agree in advance on the exact time, exact hour and exact meeting place, and we cannot cancel the agreements, because it is very difficult,” one resident told us.

“We write notes, leave them. We use coded language.”

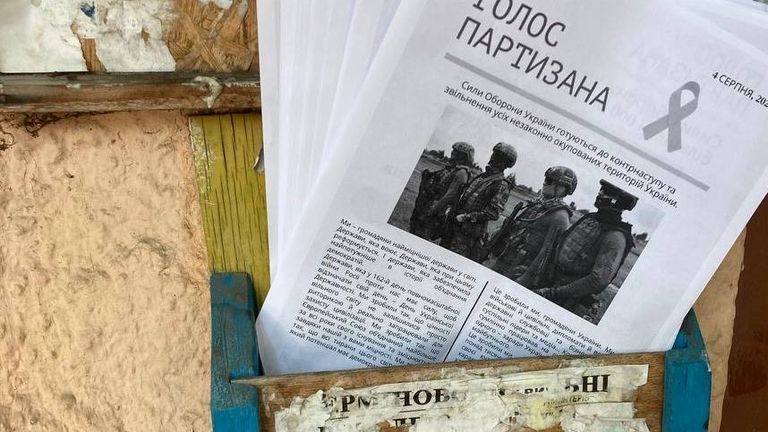

A resistance newspaper has recently been launched – it is pushed through letterboxes after dark and Ukrainian resistance inside the city keeps people updated with the location of Russian checkpoints.

We’ve spent weeks speaking to people who have recently escaped from Kherson and heard their stories of Russian occupation.

They told us accounts of people disappearing every day and rumours of a Russian crematorium to burn the bodies of Russian soldiers to cover up their losses and to get rid of the corpses of Ukrainians they tortured and killed.

“Black cars come in the middle of the night and take people away,” one resident said. Some return weeks later, and many have never been seen again.

Basic services – food and medicine – are either in short supply or now prohibitively expensive and life is becoming “desperate”, we were told.

Scarcity of affordable meat has turned people vegetarian, and one person we spoke to said they are now “on the verge of starvation”.

“There is almost no medical care left there, medicines are a big problem,” Liliya told us from Odesa.

Subscribe to the Ukraine War Diaries on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify and Spreaker

She had just arrived from Kherson and had to pass through 19 Russian roadblocks before she could escape.

“Now they have started importing food products from [Russian-occupied] Crimea, but they are very expensive,” she said. “This is the problem – the products have appeared, but you can’t buy them because you don’t have money.”

They all speak about living in fear of the Russian occupiers.

“It’s scary,” says Olena. “You don’t know what’s in their heads. You don’t know what they will do to you. You are afraid to say something. You always filter your speech because you can’t call a spade a spade. Maybe there is a Russian soldier sitting next to you on a bench listening to you.

“We never use names and exact addresses in conversation and correspondence, it is forbidden. Sometimes we agree on code words during a personal meeting.”

Olena continued: “If you mention the movement of enemy equipment, then you must delete all correspondence so that you have nothing on your phone. Because you can be stopped on the street and asked to show your phone.”

She told us stories of people who are taken and held in basements and electrocuted for displaying the Ukrainian flag.

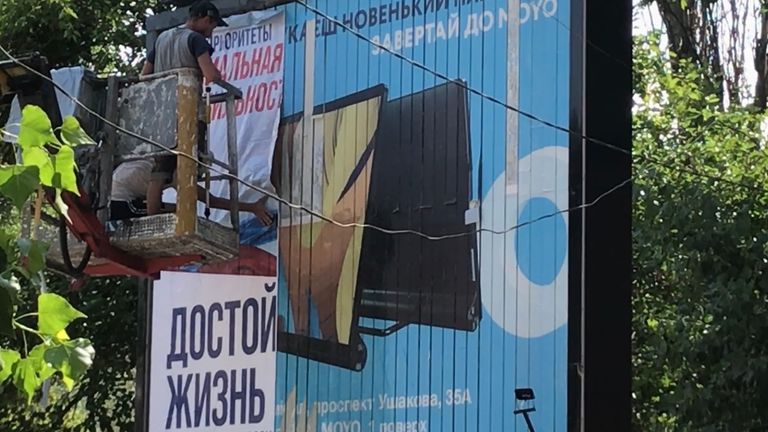

Despite this, the yellow and blue colours of Ukraine have been sprayed on walls and painted on to pillars in defiance of the occupation.

After trying many different routes, and failing, we finally made contact with someone still inside Kherson.

Dmytro, not his real name, is a journalist and unable to tell the story of his city himself, so he asked us to.

Over a fragile internet connection, he pleaded for the world not to forget Kherson.

“I understand that for people it is somewhere far away,” he said. “Maybe they are tired of reading about Ukraine every day in the news. We still want to reach every European, every citizen of the world, so that they talk about us, know about us, in particular about Kherson.”

He said that in the suburbs, Russian soldiers walk through the streets drunk, “a bottle of alcohol in one hand, a machine gun in the other”.

Perhaps in anticipation of the coming counteroffensive, Dmytro said that the behaviour of Russian soldiers had changed in the past couple of weeks.

Read more:

Longer range missiles sent by US and UK are making Russia change tactics

HIMAR system: The new US weapon being used by Ukraine against Russian targets

“There is a checkpoint at almost every intersection,” he continued. “All cars and buses are checked. Everyone is asked for their passports. They tear down garage doors and gates. They are looking for weapons, they are looking for some equipment. They are very afraid of partisans.”

It has been widely reported that the families of Russian soldiers who moved to Kherson in the days after it was captured have now left, fearing a counteroffensive. And we have been told by Ukrainian military sources that Russian commanders in Kherson city have withdrawn to the other side of the river.

Dmytro said: “To be honest, if maybe two generals or five colonels left Kherson, it’s not very noticeable. But the ordinary soldiers, the Russian occupiers, have begun to behave very insolently.

“It’s clear that they have absolutely no discipline. This indirectly confirms that the top officers must have escaped. But no one saw it, because it is impossible to see. How they got to the other side [of the Dnipro river] must have been some kind of secret operation.”

Sky can’t independently verify these accounts. The Russians deny the claims, but they are from multiple sources over the course of several months.

Longer-range HIMARS missiles, donated by the US and UK, have allowed Ukrainian forces to hit strategic targets further away than previously.

The targeting of the three road and rail bridges that cross the Dnipro River in Kherson has been a deliberate strategy to cut off resupply routes and to put fear into the Russian soldiers.

It’s working. The balance in Kherson is slowly tipping in favour of Ukraine.