The Oxford University-AstraZeneca vaccine is a collaboration between a pharmaceutical giant and an ancient institution aiming to become as adept at monetising its discoveries as it is at making them.

It is a combination that could hasten the defeat of COVID-19 and may, in time, net the university and some of its leading researchers a share of more than £74m.

It also casts light on the relationship between publicly-funded academia and private finance that increasingly drives scientific innovation, often to the benefit of patients and shareholders, as well as the disquiet of those who mistrust the role of the private sector.

Latest coronavirus updates from the UK and around the world

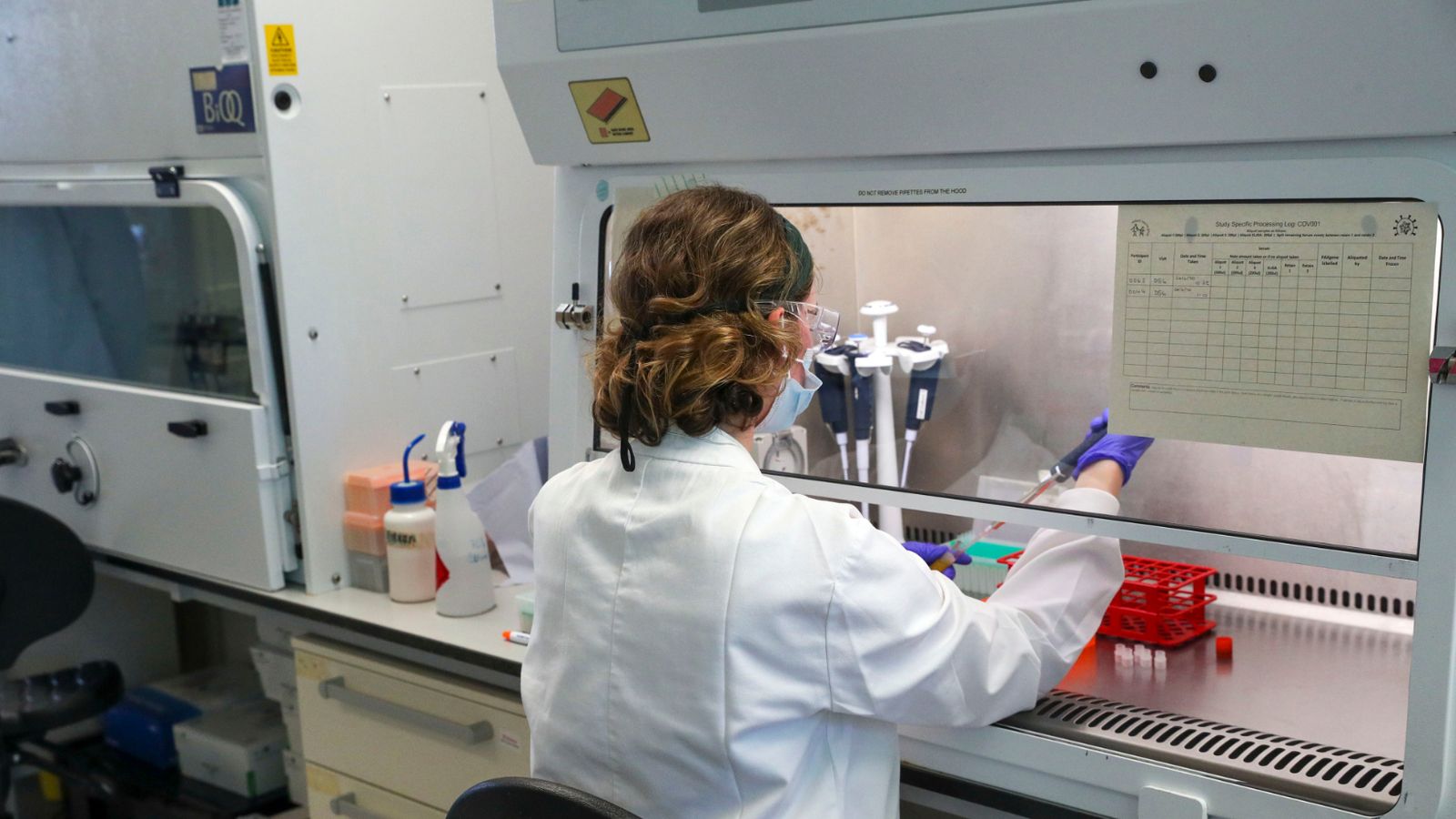

The brains behind the vaccine are based at Oxford’s Jenner Institute – named after Edward Jenner, creator of the smallpox vaccine, and part of the faculty of medicine.

Chief among them is Professor of Vaccinology Sarah Gilbert, whose ongoing research left her ideally placed to tackle COVID-19 when it emerged as a global pandemic at the turn of the year.

Her focus has been developing vaccines that use viral vector “platform technology”, essentially a vehicle that can be adapted to carry genetic material from a given disease required to trigger an immune response.

Crucially, it is adaptable and allows rapid vaccine development.

Her motivation is to save lives by providing a vaccine that can beat back the coronavirus and normalise social and economic life around the world.

But it may also prove highly rewarding courtesy of a structure, encouraged by the University of Oxford, designed to maximise and monetise the benefits of academic innovation.

At Professor Gilbert’s insistence, AstraZeneca has committed that the vaccine will be made on a not-for-profit basis as long as COVID-19 is classified as a pandemic, and will remain so when sold to developing nations.

Should the disease recede and the vaccine become an annual defence against COVID-19 sold at a profit, Professor Gilbert, her close colleagues, the university, and a range of private and corporate investors – including Google’s parent company Alphabet – all stand to benefit.

Before COVID, the rights to develop and manufacture the vaccine were owned by Vaccitech – a commercial spin-off founded in 2015 by Professor Gilbert and her colleague Professor Adrian Hill, a geneticist and the director of the Jenner Institute.

As part of the deal, the university retained a 50% share of the rights.

Oxford encourages its researchers to form private companies in order to attract outside investment in its innovations and allow it to share the financial benefits, rather than see them all pass to the private sector.

Since 2016, it has been a partner in the world’s largest university venture capital vehicle, Oxford Science Innovation (OSI), which has raised more than £600m for investments in life sciences, AI and deep tech.

OSI is a major shareholder in Vaccitech, and its investors include GV (formerly Google Ventures), the Wellcome Trust and Fosun, the Chinese healthcare conglomerate that owns Premier League club Wolverhampton Wanderers.

Professor Gilbert and Professor Hill remain employees of the university and – until September, when Professor Gilbert stepped down from the Vaccitech board to focus on the vaccine – directors of the company. Between them, they still own around 10% of Vaccitech.

When it became clear that the coronavirus would demand a global vaccination programme running to billions of doses, the university and Vaccitech accepted they required a larger partner to handle manufacture and commercial processes.

After negotiations with several potential partners, acknowledged as fraught by some of those involved, Vaccitech agreed to pass its rights back to the university, allowing Oxford to do an exclusive deal with AstraZeneca.

According to figures first reported by the Wall Street Journal, AstraZeneca paid the university an up-front fee of $10m (£7.4m) and has promised a further $80m (£59.4m) in “milestone payments”.

AstraZeneca will only take a profit when COVID-19 is not a pandemic, a decision it says will be based on the views of a range of independent bodies.

When that moment comes, the university will receive royalties of 6% on AstraZeneca’s vaccine sales. It is reported Vaccitech will receive 24% of those fees.

AstraZeneca estimates it will spend $6bn (£4.5bn) producing the three billion doses it has promised globally by the end of 2021. Of that, $1bn (£740m) is “non-manufacturing” costs, including licensing, the cost of trials and regulation, and pharmacovigilance, the ongoing monitoring of safety. A further $5bn (£3.7bn) covers manufacturing.

It is expected governments will be charged $3-$4 (£2.20-£2.97) for every dose – around a tenth of the price of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

Manufacture and supply deals have been negotiated by its commercial teams around the world, with partner institutions and companies in India, Russia, Latin America, the US and Australia.

Oxford University has received £65.5m of funding from the Vaccines Taskforce, leaving it open to criticism that public funds are boosting private profits.

AstraZeneca points out it will not initially take a profit. A further counter is that taxpayer funding de-risks the private investments required to speed up development.

For example, the three stages of clinical trials for COVID-19 vaccines are being conducted in parallel rather than in series. And AstraZeneca, like Pfizer, has manufactured large quantities of vaccine “at-risk” before it has received approval from regulators around the world.

Vaccitech’s chief executive Bill Enright would not comment on contractual negotiations or the finances of the vaccine development, but he defended the notion of private-public partnerships.

“Institutions are really good at discovery early development, but most of them do not have the expertise in product development, and doing what it takes to bring a product to market through phase two and phase three trials. That gets expensive and universities don’t want to pay for that,” he told Sky News.

“So seeking funding from elsewhere, from venture capital groups that are willing to take these kinds of risks and expense, for appropriate rewards, is a great way of delivering innovation.

“Some would argue that because the government has provided funding some of this might not be appropriate, but that funding allows the companies involved to take the appropriate risks.”

Vaccitech may now be a spectator as the first iteration of the COVID-19 vaccine is developed, but it could again play a central role in future. It retains the exclusive rights to the next phase of the viral vector technology that could drive the second generation of COVID-19 vaccines, and has received £2.3m of public funding to develop it.