Critics of the National Security Law (NSL) imposed by Beijing on Hong Kong have described its powers as sweeping – and today authorities swept wide.

More than 50 pro-democracy figures have been arrested under the law.

It is the largest, most high profile, most significant crackdown since the NSL came into force in June last year.

Politicians, lawyers, journalists, academics and pollsters have been detained, their legal offices and newsrooms raided. They all potentially face life in prison.

For those worried about Hong Kong’s deteriorating freedoms, it will look less like a law enforcement action than a purge.

If the scale of the crackdown is astounding, the apparent justification is even more so.

Reports from Hong Kong media said that most of those arrested were accused of “subverting state power”.

Their alleged offence was to hold unofficial primaries in July before elections to the Legislative Council, Hong Kong’s parliament – elections since postponed. Almost all those arrested were involved in the primaries in some way.

Pro-democrats had been aiming to win 35 seats, a majority in the 70 strong LegCo.

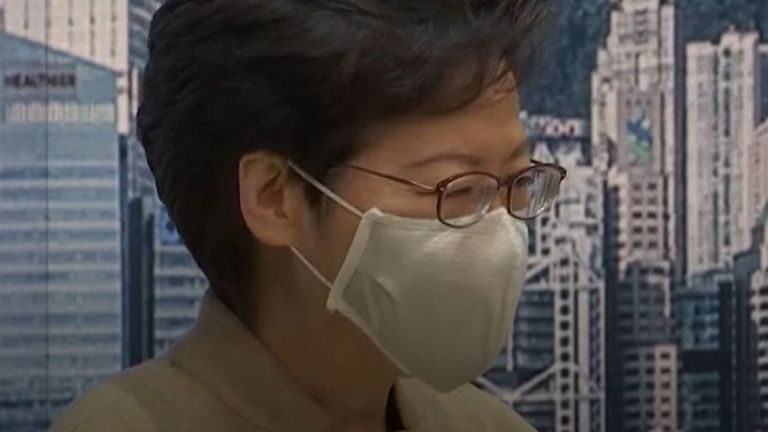

At the time, Hong Kong’s chief executive Carrie Lam warned that holding the primaries could constitute an act of subversion.

It was certainly a novel definition of subverting state power: aiming to win seats in an election.

Some candidates had vowed, if they won a majority, to block government bills, including vetoing the budget.

Most in the West would assume that is precisely the job of a political opposition. And legal scholars in Hong Kong have argued these rights are enshrined in Hong Kong’s mini constitution, the Basic Law.

But subversion is drawn widely under the NSL. Anyone “seriously interfering in, disrupting, or undermining the performance of duties and functions in accordance with the law by the body of central power of the People’s Republic of China or the body of power of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region” can be found guilty.

If that is the basis for today’s arrests, disrupting the performance of the government apparently includes the opposition voting against it. Not even that: it includes political candidates, not yet elected or even sure to be elected, saying they might vote against the government.

The arrests are the start of the process. Prosecutors will decide who to charge and then it is up to the courts.

Those arrested may have some hope there. Hong Kong’s courts have dismissed many of the charges brought against protesters under older laws and Hong Kong’s outgoing chief justice – the territory’s top judge – reaffirmed the commitment to the rule of law.

It may not be enough, though. Those charged under the NSL can also face trial on the Chinese mainland. And China’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office has loudly proclaimed the need for “judicial reform” in Hong Kong itself.

Chinese Communist Party officials described the NSL as “a sword”. It’s starting to look more like a hammer. This is its latest, heaviest blow. It is unlikely to be the last.