“Look up here, I’m in heaven,” sang David Bowie. “I’ve got scars that can’t be seen.”

The song is Lazarus, a track from the album Blackstar, released just two days before he died of liver cancer on 10 January 2016, exactly five years ago.

Was the lyric another case of Bowie being one step ahead of the world by predicting his own death? Perhaps we were supposed to see clues in the Blackstar video, in which the skeleton of a dead astronaut floats away into outer space.

The demise of Major Tom from Space Oddity? Nobody knows for sure.

But when I think about that day, I realise it’s the only time I’ve ever felt utterly bereft by the death of someone I’ve never met. This feeling is illogical, but real. It’s as if something about your own personal history has altered.

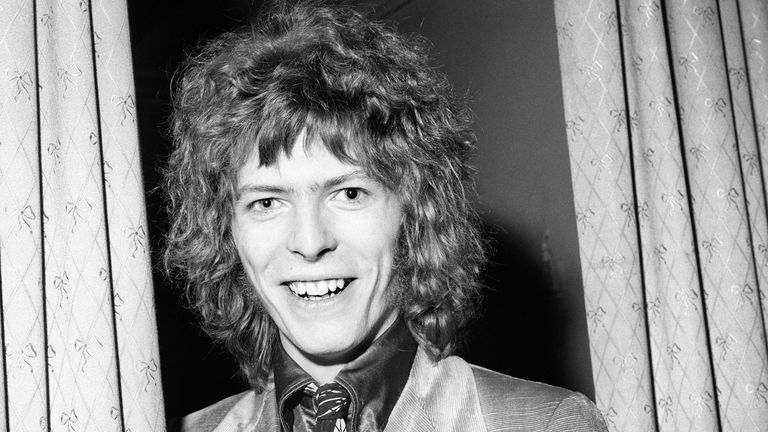

For teenage fans from the drab 1970s suburbs, Bowie offered a glimpse of extravagance, even decadence, and a thrilling soundtrack to our lives. We were hooked for life.

When you look back at his past, you realise Bowie was a master at understanding the future.

During the first rush of the Black Lives Matter protests last summer, someone shared an interview he did with MTV in 1983, which I’d not seen before.

He turned the tables on interviewer Mark Goodman by asking him questions about why there were so few black artists on the station. He was told that towns in the Midwest might be “scared to death by Prince… or a string of other black faces and black music”.

It’s jaw-dropping to watch this interview today.

Goodman said MTV had to choose music that suited all of America, and questioned what the Isley Brothers might mean in those days to a 17-year-old. Bowie came back, polite but pointed: “I’ll tell you what the Isley Brothers or Marvin Gaye mean to a black 17-year-old. Surely he’s part of America as well.”

He went on: “Should it not be a challenge to try to make the media far more integrated?”

Goodman had to agree. It’s a long road still being travelled today.

More frivolously, when you watch the 1980 video for the track Ashes To Ashes, you might think it was Bowie who invented the iPad, 30 years before Apple.

The video was, at the time, the most expensive and technologically sophisticated any artist had made. On two occasions, Bowie’s Pierrot character holds up a tablet with video playing. Surely it must have given people ideas…

Bowie saw what was coming. He was a slayer of convention and a champion of individualism.

His embrace of sexual ambiguity suggested people could just be who they wanted to be, long before the evolution in gender fluidity we see today.

I’ve looked back this week at his interview with the BBC’s Jeremy Paxman in 1999, at a time when we were all just getting used to “surfing” the internet. Paxman wondered whether the claims being made for the internet were not hugely exaggerated. He raised a quizzical eyebrow at the answer.

“I don’t think we’ve even seen the tip of the iceberg,” said Bowie. “I think the potential of what the internet is going to do to society – for good and bad – is unimaginable. We are on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying. It’s going to crush our ideas of what mediums are all about.”

I saw the interview at the time and didn’t entirely understand what he meant. A decade later, we all got it. Bowie’s grasp of the future had already envisaged that the internet would carry infinite content and provide effortless interplay between users and providers.

In 2002, he told the New York Times that the days of mass sales of CDs would one day end.

“Music is going to become like running water or electricity – the absolute transformation of everything we have thought about music will take place within 10 years.”

He told his fellow artists that they’d better get used to doing a lot of touring to make their money, because future streaming services would dominate music. Spotify launched in October 2008, and Bowie had proved to be far-sighted yet again.

His insights were the product of an insatiably curious mind.

He read Nietzsche, William S Burroughs and the poet Khalil Gibran. He was influenced musically by Little Richard, John Coltrane, Bob Dylan and The Velvet Underground. He was fascinated by George Orwell, Anthony Burgess, Andy Warhol and Salvador Dali.

These, and many other influences, were filtered through the multiplex of his brain and erupted in a frenzy of creativity, which delivered 13 albums in 11 years between 1969 and 1980.

Bowie electrified the 1970s to the same extent that The Beatles helped define the 1960s, feeding off the social fluctuations and paranoias of the age.

We could have lost him so much earlier than we did. His mid-’70s tour of the United States was relentlessly fuelled by cocaine. Pictures of him at the time reveal a pale, cadaverous figure, permanently on the edge – and sometimes over it.

Yet the creativity was never stifled. He managed to switch mid-tour from the rock-and-roll of Diamond Dogs to the soul of Young Americans, which he wrote and then recorded in Philadelphia, while on the road, and under the influence.

He has said himself that he doesn’t know what might have happened to him, had he not abandoned the American hedonism for a quieter life in Berlin. His Berlin trilogy – Low, Heroes, and Lodger – was the result of European influence and his embrace of electronic and ambient music in collaboration with Brian Eno.

It was a ’70s innovation which helped usher in the music of the ’80s.

There is at least compensation for the loss of such an extraordinary creative force. The music which sold 140 million albums is still here. His influence on music, art, fashion and style can’t be erased.

He sang on Blackstar: “Something happened on the day he died. His spirit rose a metre, and stepped aside.”

I’m not sure there’s anyone out there to take his place.