As the row over vaccine supplies heated up this week, the UK government stuck to a simple line.

Ministers and officials repeatedly said they do not want conflict over vaccines. Yet, at the same time, they stated their confidence that they would get the doses they needed.

“We’re very confident in our supplies, we’re very confident in our contracts and we’re going ahead on that basis,” the prime minister declared on Wednesday. Behind the scenes, the message is the same. As far as it is possible to tell, the confidence is real.

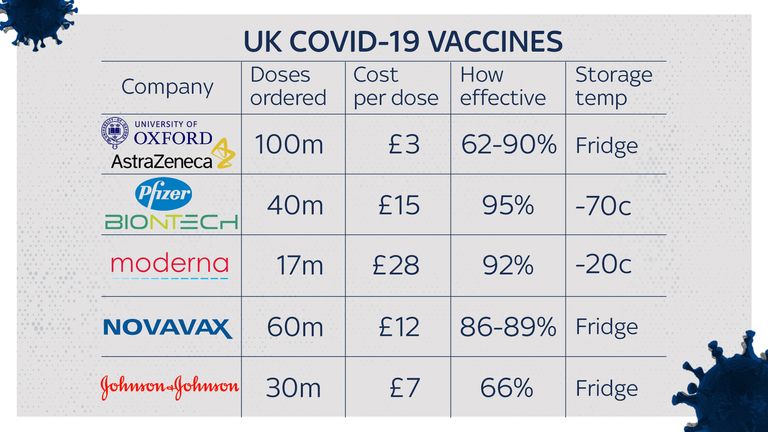

Its source is the UK’s largest vaccine order: its agreement with AstraZeneca for 100 million doses of the vaccine developed at Oxford.

Ministers believe this arrangement will keep the supply of vaccines flowing to the UK, even in the unwanted event of a vaccine trade war.

Partly, this is a matter of technology. Unlike the Pfizer vaccine, which is largely manufactured in Europe using specialised technology that would be almost impossible to replicate elsewhere, the process used to make the AstraZeneca vaccine is – in vaccine terms – relatively flexible.

“The Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine is based on a more established technology, meaning that there are a wide range of suppliers for all the materials and consumables that go into this vaccine,” said Dr Zoltan Kis of Imperial College London’s Future Manufacturing Hub, which is investigating how to produce large amounts of vaccines very quickly.

“That means the company is not restricted to one specific supplier. In case they have to not use those [European] suppliers, they would have the option of switching to a supplier outside of the EU.”

Switching suppliers would almost certainly lead to delays as new arrangements were made and certified. (Regulatory checks to bring a vaccine manufacturing facility online can take weeks, if not months) But in a worst case scenario, it would at least be possible.

However, the real source of the government’s confidence is its contract with AstraZeneca, which ministers believe commits the pharmaceutical company to delivering UK doses first – a fact confirmed by AstraZeneca boss Pascal Soriot in an interview with Italian newspaper La Repubblica.

Whether that guarantee will hold up under a challenge remains to be seen. Yet, according to a former Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) adviser, the UK nearly missed out on this degree of security.

That is because the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine was very nearly the Oxford-Merck vaccine – and under the terms of the agreement with the American pharmaceutical giant, there were no guarantees of supply.

The episode played out against the backdrop of the first phase of the pandemic. During March and April 2020, the University of Oxford negotiated a deal which would allow Merck to manufacture and distribute the vaccine it was in the process of developing.

The arrangement made sense. Unlike British-Swedish AstraZeneca, Merck had experience in making vaccines. Its senior executives had links to Oxford scientist and government adviser Sir John Bell.

Yet when the contract reached Matt Hancock’s desk, the former adviser said, the health secretary refused to approve it, because it didn’t include provisions specifically committing to supply the UK first.

The fear was export controls – not from the EU, but from the US. Mr Hancock was worried that president Trump would stop vaccines from Merck leaving the country.

With the university and Merck “as close to signing on the dotted line as they could be”, he stopped it going ahead, because he didn’t want to risk the intellectual property rights for the Oxford vaccine ending up in the hands of a single American company.

“He was just meant to confirm he was happy, and then it would have happened immediately,” said the former adviser. “But he wasn’t, and overruled officials to block the deal.”

Reports have suggested that the Oxford scientists were unsure whether the deal with Merck had strong enough provisions for supplying poorer countries with vaccines. Mr Hancock’s objection was more local and political. He wanted to make sure there was enough for UK citizens. The rest of the world could come later.

German MEP Peter Liese said the UK was behaving “like Donald Trump” by trying to guarantee it would receive vaccine doses first. In reality, according to this account, it was fear of Trump – or Trump-like behaviour – that prompted the government to seek additional security.

To see how quickly competition for scarce resources could escalate into conflict, Mr Hancock and his advisers only needed to look at their own recent experience. At the same time as negotiations were developing between Oxford and Merck, DHSC was desperately hunting for ways to replenish its threadbare stocks of Personal Protective Equipment.

In NHS hospitals, nurses were wearing bin bags for protective clothing. Yet the scramble to get hold of PPE was made more difficult by European export controls.

In early March, Germany imposed a temporary ban on PPE leaving the country; shortly after, the EU introduced a similar measure (as did the UK, which has also maintained restrictions preventing hundreds of medicines leaving its borders without permission).

The PPE crisis grew so serious that one former Downing Street insider says it almost cost Mr Hancock his job. It also gave the health secretary a powerful reminder about the Hobbesian nature of global politics in a pandemic.

The other reminder came from a more surprising source: Steven Soderbergh’s film Contagion.

Released in 2011, the film followed the path of a pandemic caused by a SARS-like respiratory virus, which killed millions and caused widespread social unrest, until it was finally stopped by an effective vaccine.

However, when the vaccine did arrive, there was not enough of it to go around, so vaccinations were awarded by a lottery based on birthdates.

The episode stuck in Mr Hancock’s mind. “He would keep referring to the end of the film,” says the former DHSC adviser.

“He was always really aware from the very start, first that the vaccine was really important, second that when a vaccine was developed we would see an almighty global scramble for this thing.”

At other times during the pandemic, it has felt as if the government was scrambling to keep up with events. Former insiders in both DHSC and Downing Street acknowledge that they struggled to find a strategy to deal with a virus that spread so rapidly without symptoms.

Yet from the very start there was a focus on vaccines. According to the former adviser, the DHSC started work on it in January, before there was even a case of COVID-19 in the UK.

Back then, scientists said it was unlikely a vaccine would be developed within 18 months, let alone a year – and that they would probably be around 50% effective when they arrived. Yet, encouraged by Mr Hancock, the Department for Health pushed ahead, in order to make sure everything was ready for the moment the vaccine arrived.

“Every extra day it takes to deliver a vaccine comes with a human cost and an economic cost,” Mr Hancock told officials in April. “I don’t care if people think it’s years away – every day we save now is lives we will be saving in a year’s time.”

Every process had to be accelerated. At one internal meeting in April, a group of vaccine officials were asked to assume that the vaccine would arrive in a year’s time. For that scenario to play out well, what would they need to be doing now?

The replies, said one person who was present, were “mind-blowing”. One expert warned that there would almost certainly be a shortage of glass vials. Another said that production would be difficult. A third raised the issue of supply chains.

The normal way of doing things would be to fix these issues once the vaccine was ready. But these weren’t normal times – so the government determined to resolve them in advance.

Production lines were worked out. Arrangements were made for vaccine “fill and finish”. Suppliers for glass vials were found and contracts were secured.

At the same time, officials realised that although there was a Therapeutics Taskforce, overseeing the search for and deployment of treatments for COVID-19, there was no comparable body for vaccines. The Vaccine Taskforce was set up: a month later, Kate Bingham was appointed as its head, and given the task of ordering the vaccines themselves.

As he pushed his team to go faster, Mr Hancock took inspiration from another early failure. In March, the government bought two million antibody tests from two Chinese companies, paying for them up front. Boris Johnson promised that the upcoming shipment would be a “game changer”. In reality, they turned out to be unusable.

But the principle of taking a risk on potential new solutions before they were proven was, Mr Hancock decided, the right approach. That might lead to more mistakes – arguably, it did, most notably with the first contact tracing app – but he believed it would produce the best results overall.

Subscribe to the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

The attitude matched that of other senior officials, including former Downing Street adviser Dominic Cummings. According to one public health official who worked on vaccines and mass testing, the mantra in central government was: “No regrets.”

“That’s what they all said,” the official recalled. “They were drawing up plans for vaccination to start in October. We thought it seemed a bit optimistic, but they kept on saying, ‘We don’t want to have any regrets’.”

Some might say that waiting for a vaccine to arrive is not a strategy for managing a pandemic, and the UK’s desperation for supplies of it is indeed a mark of its failure to control the virus by alternative means. It is also true that although the UK is off to a fast start, there is still time for things to go wrong. After all, it got off to a fast start with testing too.

Yet, for now, the government is confident it will have what it needs. This confidence, some say, is precisely what has enabled it to play down the prospect of a vaccine trade war, rather than enflaming it. Another lesson about the nature of pandemic politics: without security, there can be no peace.