Boris Johnson is due to unveil his roadmap for lifting the current lockdown, with rapid mass testing set to be a key part of the prime minister’s plan for easing COVID restrictions.

Ministers have said lateral flow tests will be used to crack down on fresh coronavirus outbreaks once national restrictions are loosened.

It has also been suggested the same tests will assist in the return of pupils to schools and could even allow venues such as nightclubs and theatres to reopen their doors.

So, what are lateral flow tests?

Sky News has looked at the different types of COVID-19 tests available.

There are two different strands of testing – one is to find out if a person currently has the disease, and the other determines if they have had it and have built up antibodies.

PCR testing and antigen testing (often confused as the same kind of test) are different methods of testing, but both ascertain whether a person has COVID-19 at the time.

PCR testing

Swab testing

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is currently the most common form of testing in the UK and is seen as fairly reliable.

Lighthouse Labs, which are dedicated to COVID-19 testing, found PCR tests are around 99% effective.

These types of tests have been used by the NHS in their testing centres around the country for the past few months and are the tests sent out by the NHS to people who have symptoms.

For PCR tests, a swab is used to collect an RNA sample (the nucleic acid that converts DNA into proteins) from the patient’s tonsils and inside their nose.

RNA is collected as it carries the genetic information of this specific virus.

This is then sent to a laboratory where the sample is heated and cooled so it multiplies into larger quantities of DNA.

Bioscientists can then see whether the SARS-CoV-2 virus (the virus that causes COVID-19) is present.

Because of the process, PCR test results take about two days.

LAMP testing

Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) is a similar process to PCR testing but produces many more viral RNA copies at a constant temperature instead of heating and cooling so can have a result much quicker – within a couple of hours or even faster.

A swab is used to take samples from the nose or throat, or mucus from hard coughing can also be used. The swabbing does not need to be as vigorous as it is for the PCR test.

The samples are then placed in vials of reagents (substances that produce a chemical reaction to detect the RNA), then heated in a special machine for 20 minutes.

The machine then analyses the sample and confirms if there is any SARS-CoV-2 RNA.

LAMP technology has been used to test NHS staff in Liverpool as part of a pilot in the city to “inform a blueprint for how mass testing can be achieved and how fast and reliable COVID-19 testing can be delivered at scale”, the Department of Health and Social Care said.

In mid-September, LAMP testing was part of a £500m funding boost after a successful pilot across Hampshire hospitals, GP test hubs and care homes.

90-minute PCR test

Machines that can deliver on-the-spot genetic testing are being used to collect RNA for PCR testing, which can also detect the common flu.

The RNA, taken using swab samples placed into a cartridge, is inserted into the machine which carries out a PCR test and then identifies if the virus is present.

A successful pilot test across eight London hospitals using British start-up DnaNudge’s machines is being rolled out to urgent NHS patient care and elective surgery settings UK-wide, plus out of hospital settings, with the plan to deliver 5.8 million tests.

No-swab saliva test

Patients can do this test at home by collecting about two millimetres of saliva into a sample pot, then sending it off to a laboratory.

The sample gets tested using LAMP technology in a lab and the result is then texted to the person.

It still takes about 48 hours but there is no need for a patient to leave their home or stick a swab down their throat or up their nose.

A government-funded trial in Southampton was expanded from GPs to the city’s university staff and students, and four schools.

Antigen testing

These tests look for antigens – proteins on the surface of the virus.

Antigens can easily be detected in saliva and laboratory testing is not necessary, so can be done in places such as care homes and without a medical professional.

Results can be provided more quickly than PCR tests, with some systems already available and dozens more being developed.

However, an ongoing review of one antigen COVID test found that sensitivity dropped when done by members of the public instead of healthcare staff – meaning there is a higher chance of false negatives when the tests are used by self-trained users until they develop more experience.

The preliminary report from the joint PHE Porton Down and University of Oxford SARS-CoV-2 test development and validation cell found the sensitivity of the “Innova SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Rapid Qualitative Test” dropped from 79% when used by laboratory scientists compared to 73% when used by trained healthcare staff compared to 58% when used by self-trained members of the public.

Lateral flow testing

These tests are designed to identify asymptomatic people and have been used across England after a pilot in Liverpool.

It uses similar technology to a pregnancy test.

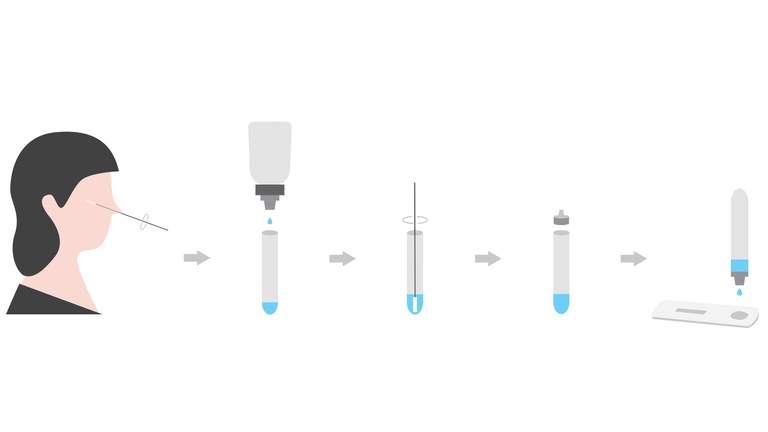

A swab is inserted into the nose or throat, then the sample is inserted into a tube of liquid for a short time which extracts the molecule that determines if COVID-19 is present.

No laboratory equipment is needed as a few drops of liquid are then dropped onto a small strip.

Within 15 minutes, the strip of paper will show up with two lines if it is positive, one line on the top if it is negative or one line on the bottom if the test is invalid.

While the test result returns very quickly, there are questions over its sensitivity, with initial tests by PHE Porton Down and the University of Oxford of the Innova lateral flow test being used in Liverpool finding 76.8% sensitivity – the proportion of people with COVID-19 who show up positive.

The team also found the Innova test had a specificity – the proportion of people without the disease who have a negative test – of 99.68%, meaning the false positive rate was 0.32%.

However, they found it detects more than 95% of people with high viral loads, with little difference between those who are symptomatic and asymptomatic.

SAGE, the government’s scientific advisory group, warned that with mass testing, false positives and false negatives could have “critical implications” for effectiveness, therefore a follow-up confirmatory test is highly important.

20-second test

Released in September, the Virolens system uses a portable machine which creates a microscopic holographic image to detect the virus in saliva samples in 20 seconds.

Developed by British companies iAbra and TT Electronics, it uses a digital camera attached to a microscope, which then runs data through a computer that can identify the virus from other cells.

The device has been trialled at Heathrow Airport, whose chief executive, John Holland-Kaye, has urged the government to fast-track the technology to be used across the UK.

Antibody testing

Antibody testing looks at whether your body has produced any antibodies to fight against the virus.

A blood test is taken from a person who has had COVID-19 symptoms that have disappeared three to four weeks before.

A lab test then takes a unique protein the virus makes and tests whether any antibodies in the blood bind to that protein.

There are pin-prick tests in development which would allow a person to submit their own blood test, but these have not been rolled out yet.

Unlike other diseases, the UK government and the World Health Organisation agree there is currently no evidence that someone with antibodies will not catch COVID-19 again in the future.

A study by Imperial College found the levels of protective antibodies in people who have had COVID-19 drop “quite rapidly”.

Another study found T-cells, which attack the infected cells, were lasting longer than antibodies – six months after infection.