Scientists are carrying out research to try to predict who might become seriously ill from coronavirus by analysing the immune response of patients.

Evidence suggests some patients become severely ill from COVID-19 after having a massive inflammatory response from their immune system, part of which is often known as a “cytokine storm”, which can lead to organ failure and death.

Others do not have the response.

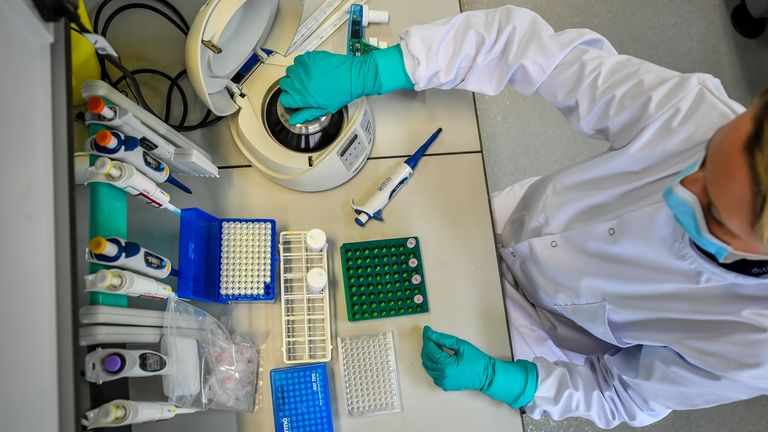

The Press Association was given rare access to the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) at Porton Down, near Salisbury, where a pilot study is examining randomised blood samples from 30 hospital patients.

Scientists will then compare how their immune systems react to the disease.

Dstl is working with the Hywel Dda University Health Board and Swansea University on the study which is looking at the activation of white cells, part of the body’s immune system, and the proteins which are present on their surfaces.

The research is using techniques such as flow cytometry which detects and measures physical and chemical characteristics of cells.

State of the art tests which are not available in hospitals are being used by Dstl.

The study is in its early stages with data and findings anticipated in the coming months.

It is hoped this analysis could help answer questions on how and why patients are affected so differently by COVID-19 and potentially even lead to new tests and treatments in future.

The project is part of a plethora of coronavirus studies being carried out by Dstl at its 7,000-acre high-security site in the Wiltshire countryside.

Projects include developing equipment such as an artificial finger to check how long the disease can survive on surfaces as well as looking at which disinfectants may be the most effective against it.

Another project in its early stages is considering whether the data gathered from shop-bought smart watches, which measure things like heart rate, could predict if someone was going to fall severely ill.

Porton Down is the oldest chemical warfare research centre in the world.

Its highly trained scientists are, with strict safety measures in place, used to handling some of the most dangerous known substances like Ebola, Anthrax, the nerve agent novichok and plague – all of which can kill.

While there was some “trepidation” in working with a new virus, scientists there have revealed how they felt proud to “step up” and be at the forefront of cutting edge science which could help keep people safe.

Amanda Phelps, a virologist with more than 20 years’ experience working in high containment labs, said: “There’s always some anxiety with something new because you don’t know necessarily how you might expect it to behave.

“Most of the viruses that we have worked on for a number of years, we understand them very well. We understand how they grow and how they will behave.

“Now, coronavirus we didn’t necessarily expect to behave in any way that was very different to any of our other highly pathogenic viruses. But we didn’t know.”

She added: “And so I guess there was a level of trepidation. But also, this is novel research, this is cutting-edge science,… so there’s also a degree of eagerness to progress,… the knowledge that’s going to enable us to inform the policy piece and to keep people safe.”

Professor Tim Atkins, who co-ordinates Dstl’s research on coronavirus, said the team was “really excited and humbled” to be involved in the work.

He hopes the research will help put clinicians on “the front foot” to provide them with information that allows them to “make early interventions and improve the outcome for patients who get severely ill from coronavirus”.

Subscribe to the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

Professor Atkins said: “What we want to do is play our role in providing data that I guess develops the common scientific understanding of this disease.

“And that ultimately is used to help patient outcomes to help globally and the United Kingdom fight this pandemic and so that coronavirus no longer represents the threat that it currently does to our way to our way of life.”

Keir Lewis, the chief investigator at the Hywel Dda University Health Board and a professor of respiratory medicine at Swansea University Medical School, described the work as a “unique collaboration” where “pooled expertise will better understand a common and deadly enemy”.

He added: “Working with the research team at Dstl has allowed specialist testing that we wouldn’t normally have.”