Detections of methane on Mars have excited scientists because, on Earth, the gas is often produced by microbes – its presence could indicate that similar life was, or is, present on the red planet.

There are potential geological processes that could produce methane too, but even before identifying the source of the gas on Mars, scientists have been trying to solve another mystery.

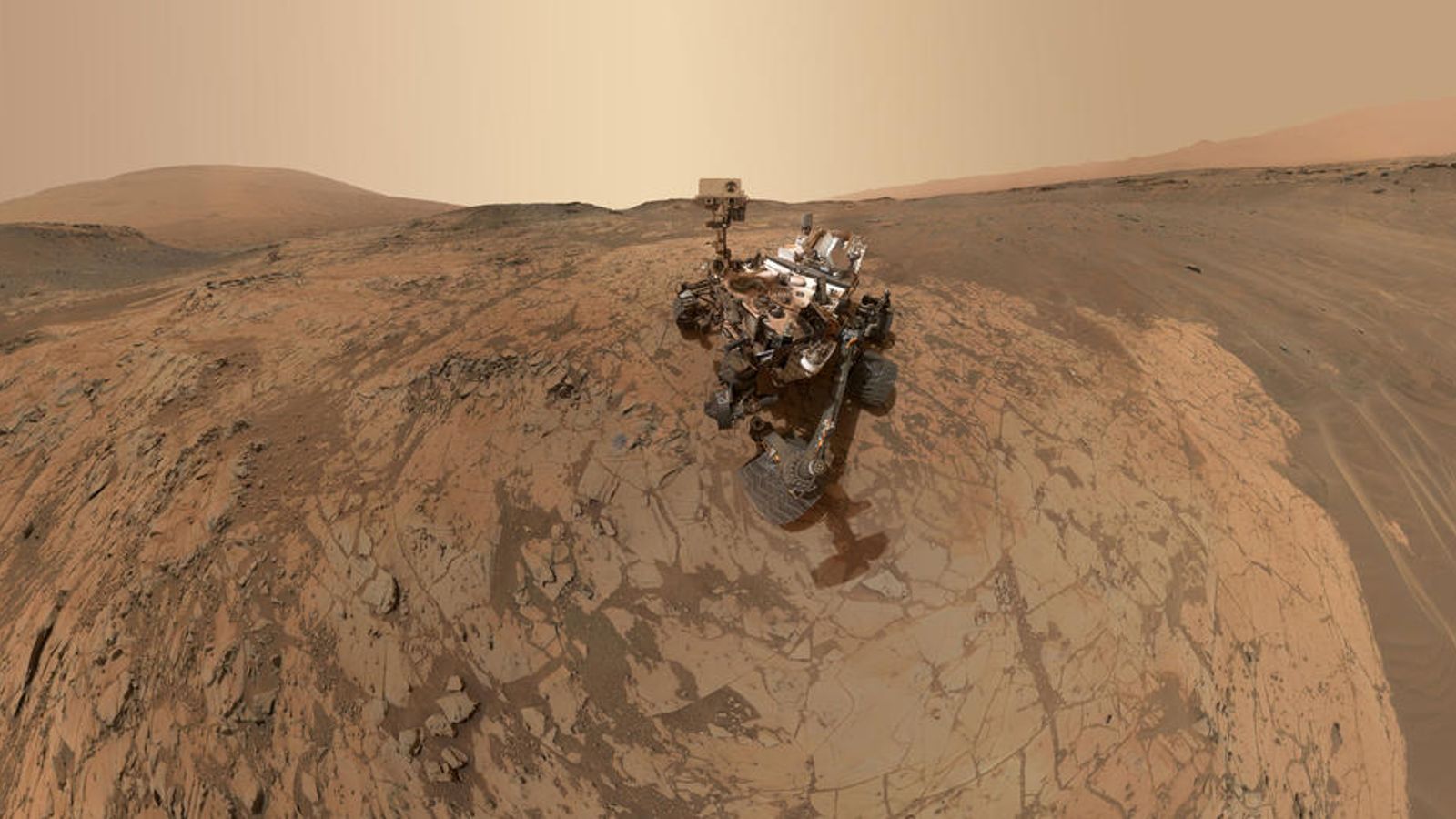

The detections of methane aren’t consistent. Some instruments, such as NASA’s Curiosity rover, have repeatedly detected the gas above the surface of the Gale Crater. Others, such as ESA’s (European Space Agency) orbiter, haven’t found any traces of methane higher up in the Martian atmosphere.

Aboard the Curiosity rover is an instrument called the Tunable Laser Spectrometer (TLS) which has detected varying amounts of methane – from less than one-half part per billion “equivalent to about a pinch of salt diluted in an Olympic-size swimming pool” to up to 20 parts per billion.

The issue can’t be one of design or malfunction. ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter is “designed to be the gold standard for measuring methane and other gases over the whole planet”, explained NASA, and yet it was finding no methane at all.

The TLS instrument is so preside, it has even been licensed for use in industrial systems and fighter aircraft to monitor for gas levels.

“When the Trace Gas Orbiter came on board in 2016, I was fully expecting the orbiter team to report that there’s a small amount of methane everywhere on Mars,” said Chris Webster, who leads the TLS instrument for NASA.

“When the European team announced that it saw no methane, I was definitely shocked,” he added.

The TLS team checked to see if the rover was releasing the gas itself somehow.

“We looked at correlations with the pointing of the rover, the ground, the crushing of rocks, the wheel degradation -you name it. I cannot overstate the effort the team has put into looking at every little detail to make sure those measurements are correct, and they are.”

At this point, John Moores, a scientist from York University in Toronto proposed a counter-intuitive solution.

“I took what some of my colleagues are calling a very Canadian view of this, in the sense that I asked the question: ‘What if Curiosity and the Trace Gas Orbiter are both right?'” Moores said.

Working with the Curiosity team, Moores hypothesised that the discrepancy between the measurements came down to the time of day they were taken.

The TLS, they realised, operates mostly at night when Curiosity’s other instruments are sleeping. As the Martian atmosphere is calm at night, any methane seeping up from the ground builds up near the surface.

The orbiter however depends on sunlight to pinpoint trace gases about 5km from the planet’s surface. As the atmosphere is more active during the day, any methane present would have been diluted to undetectable levels.

Experiments quickly confirmed that this was the case, but another mystery remained even beyond the origin of the methane: Why was it disappearing?

Methane is a stable molecule. Even without a protective atmosphere, it is expected to last for 300 years on Mars before solar radiation tears it apart.

If it is constantly seeping from all craters on the planet – something which researchers believe, as there is apparently nothing geologically unique about the Gale Crater – then there should be enough in the atmosphere for the orbiter to detect.

The researchers are now experimenting to see whether “very low-level electric discharges induced by dust in the Martian atmosphere could destroy methane, or whether abundant oxygen at the Martian surface quickly destroys methane before it can reach the upper atmosphere”.

“We need to determine whether there’s a faster destruction mechanism than normal to fully reconcile the data sets from the rover and the orbiter,” Webster said.

After that, the team can try and figure out where the methane is coming from.