Scientists from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, have announced the discovery of a major breakthrough in quantum computing.

To date, quantum scientists and computer engineers have only been able to use proof-of-concept models of quantum processors that work with just a few spin qubits, the quantum equivalent of a bit.

Now, new research published in the journal Science Advances has identified a technique which the researchers claim will enable them to control millions of these qubits.

The team considers their design the “missing jigsaw piece” in quantum computer architecture.

In a traditional computer, a bit – the single unit of information, either a 0 or a 1 – is stored in the electronic circuit of the computer itself, specifically in the capacitor of a memory cell, with the value depending on whether the capacitor is charged or discharged.

Spin qubit quantum computers replace this capacitor with a single quantum particle – the electron – and its “spin” value.

Dr Jarryd Play, a researcher at UNSW, explained: “Up until this point, controlling electron spin qubits relied on us delivering microwave magnetic fields by putting a current through a wire right beside the qubit.

“This poses some real challenges if we want to scale up to the millions of qubits that a quantum computer will need to solve globally significant problems, such as the design of new vaccines.

“First off, the magnetic fields drop off really quickly with distance, so we can only control those qubits closest to the wire.

“That means we would need to add more and more wires as we brought in more and more qubits, which would take up a lot of real estate on the chip.”

The issue is that these chips need to operate at extremely cold temperatures, below -270C, and introducing more wires would compromise the temperature of the chip and interfere with the reliability of the qubit.

“So we come back to only being able to control a few qubits with this wire technique,” Dr Pla said.

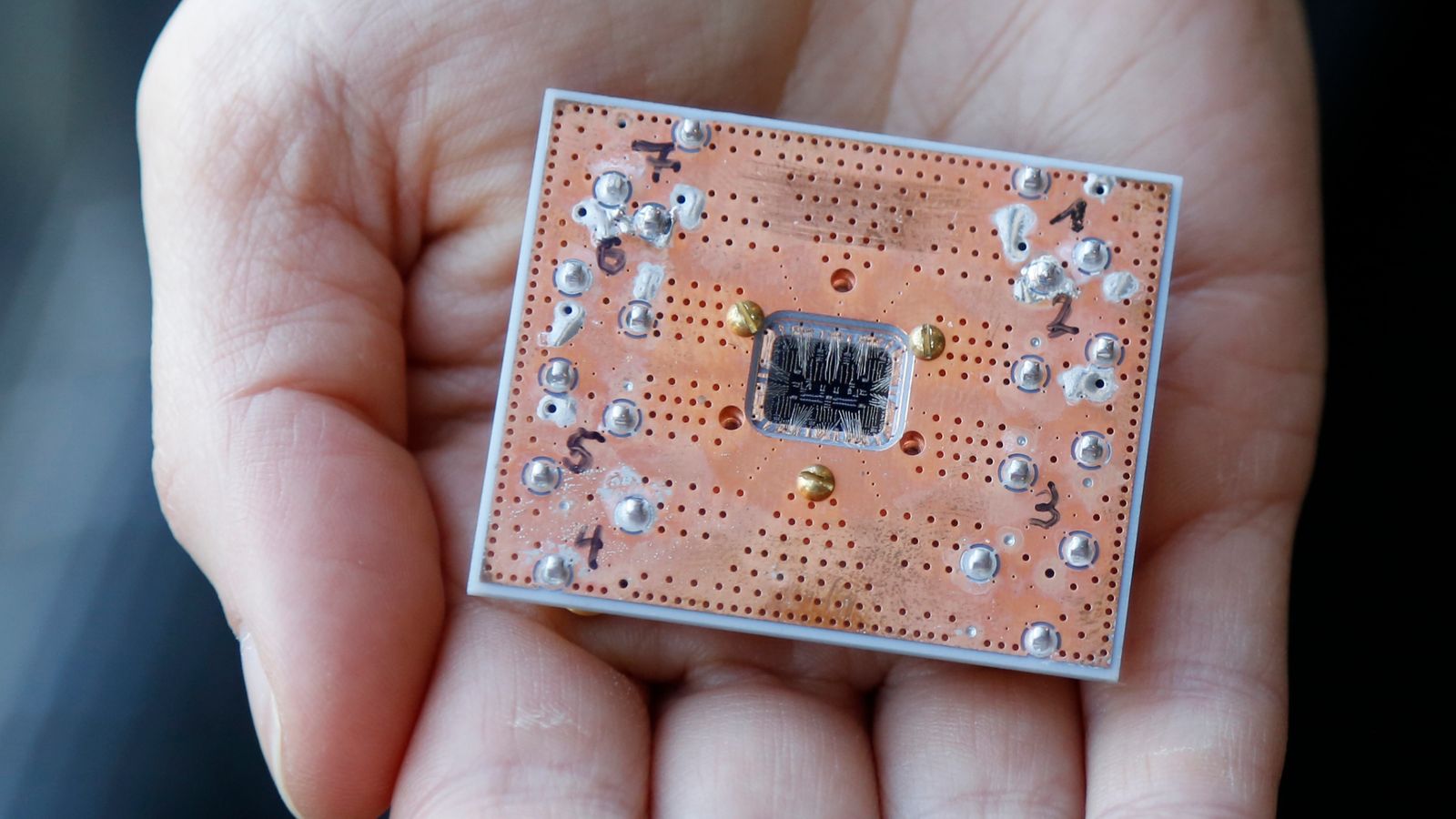

The breakthrough came in redesigning the entire structure of a chip. Instead of having thousands of control wires running across the thumbnail-sized piece of silicon, the team generated a magnetic field from above the chip which can manipulate all of the qubits simultaneously.

This had first been proposed in the 1990s, but the new research is the first practical way to achieve this.

“First we removed the wire next to the qubits and then came up with a novel way to deliver microwave-frequency magnetic control fields across the entire system. So in principle, we could deliver control fields to up to four million qubits,” said Dr Pla.

The researchers then added a new component above the silicon chip, a crystal prism called a dielectric resonator, which can be used to focus the wavelength of microwaves down into a smaller size.

“The dielectric resonator shrinks the wavelength down below one millimetre, so we now have a very efficient conversion of microwave power into the magnetic field that controls the spins of all the qubits.

“There are two key innovations here. The first is that we don’t have to put in a lot of power to get a strong driving field for the qubits, which crucially means we don’t generate much heat. The second is that the field is very uniform across the chip, so that millions of qubits all experience the same level of control.”

The team’s experiments which could allow them to control millions of qubits at the same time was a success, although “there are engineering challenges to resolve before processors with a million qubits can be made”, Dr Pla added.