If the war in Ukraine has shown us anything, it is the horrific power of conventional weapons.

Digital tools can do many things, but they cannot level a building, destroy a tank or directly end an innocent life.

If you want to stop a television tower from broadcasting, as the Russian army did in Kyiv on 1 March, then it’s quicker and easier to do it with a missile than with computer code.

‘Pretty good’ peace talks held as Zelenskyy hints at NATO concession – follow latest updates on Ukraine

Informed observers of cyber are not surprised by this dynamic. They have long argued that military terms such as “cyberwar” and “cyberweapons” fail to describe the real impact of cyber, which is most relevant in the grey zone between peace and war, where states are in conflict or competition but not actually fighting on the battlefield.

The fog of war applies in this domain as much as anywhere else, and cyber is almost certainly being used to support the Russian troops on the ground in ways we cannot see. However, at this point it is clearly following the physical bombardment, not leading it, still less working as an independent force.

This is worth bearing in mind when we consider the possibility of a Russian cyberattack on a democratic country such as the UK.

Many believe the threat is real. Russia has the capacity and the motivation.

Read more: Cyber, war and Ukraine – What does recent history teach us to expect?

Leading cybersecurity analyst Dmitri Alperovitch was one of the first people to predict that Putin would invade Ukraine. He fully expects the Russian leader to order cyber attacks as a response to economic sanctions.

“Russia’s not going to take that lying down,” he said at a recent event organised by his Alperovitch Institute think tank. “It’s going to retaliate against the West, including in cyberspace.

“They’re obviously quite busy right now, prosecuting the war in Ukraine, I don’t think they’re interested in further escalating the fight and having a cyber tit-for-tat with the West until they get Ukraine more under control, but as soon as they start accomplishing their military objectives on the ground in Ukraine they may revert back to looking at the West.

“I expect they might target energy infrastructure in Europe, they might target it in the US as well. They might go after financial infrastructure as direct retaliation for sanctions.”

Read more: Should UK be worried about an escalating cyber conflict?

Cybersecurity teams are already on high alert. Senior executives at several banks told the Financial Times they are worried about attacks on Swift, the messaging system used to send payments across borders. Fears have even been raised about attacks on nuclear power plants.

But while doomsday “cybergeddon” scenarios shouldn’t be completely discounted, experts believe they are unlikely.

“You can never rule out those major, major events. However, the larger the event, the bigger the risk for the perpetrator of provoking a very strong response,” says Emily Taylor, CEO of cybersecurity firm Oxford Information Labs.

Would a very aggressive cyberattack be treated like an act of war? That is a definite possibility, one that needs to be taken into account by any attacker.

The nature of cyber makes this kind of calculation difficult. Although cyber attacks are often described as surgical or precise, in reality, they can be extremely unpredictable. They have a tendency to spin out of control.

We can see this tendency in one of the attacks that has already taken place in Ukraine. On 24 February, a few hours before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, large parts of a network of high speed satellite services operated by American company Viasat suddenly went down.

In other developments:

• More than 100,000 Britons register interest to house Ukrainian refugees

• UK announces sanctions against 350 more Russian nationals and entities

• UK bans luxury goods exports to Russia and hikes import tariffs on products – including vodka

• Briton who travelled to warzone to join military fight against Russia leaves over ‘suicide mission’ fears

• Employee interrupts Russian news programme with anti-war slogan

The cause appeared to be a cyber attack, apparently aimed at Ukrainian military communications. But, whether accidentally or not, organisations in other countries were affected.

In Germany, thousands of wind turbines were forced offline. In France, tens of thousands of internet users found their connection had disappeared.

This kind of volatility makes cyber an unwieldy tool in a conflict where precise signalling is so important. For this reason, says Ms Taylor, states tend to use it to disrupt and degrade rather than directly attack.

“We do tend to see most state actors play in the subversive, plausibly deniable space, even if the denial is very implausible in cases,” she says.

“That’s really where cyber is safest for a state to use, because there’s still so much uncertainty about what the consequences are.”

Russia has long experience in this domain, often acting through its network of cybercriminal gangs.

Read more: Russia is a cyber power – does that mean a cyber war is coming?

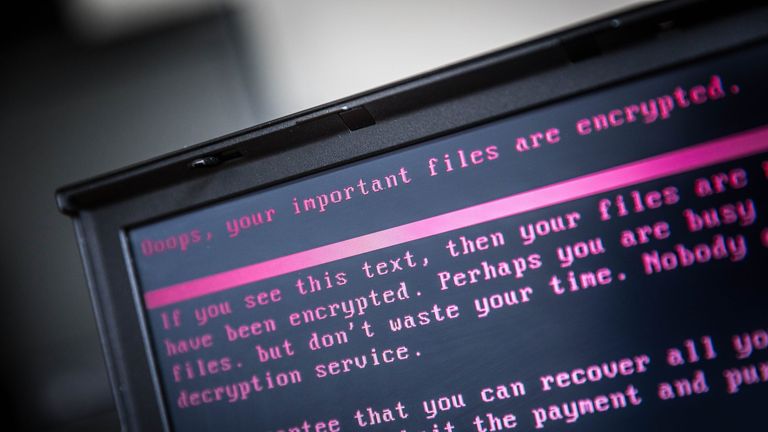

The consequences of these attacks can be severe. Last May, hackers linked to Russia stopped the flow of oil through the largest fuel pipeline in the United States. That same month, Ireland’s healthcare administrator had its IT systems shut down by the Russia-based Conti ransomware group.

Cyber ‘often less dangerous than it appears’

Yet, at the same time, we shouldn’t overestimate the threat of cyber. Despite the hype, it is often less dangerous than it appears.

Just yesterday, Israel announced that several of its government websites had gone down following “one of the largest cyber attacks in history.”

On closer inspection, this attack turned out to be a distributed denial of service attack – a nasty form of cyber vandalism, no doubt, but not the kind of attack that would have bothered Israel’s sophisticated cybersecurity services for too long.

Even some of the most notorious attacks in history actually had relatively little effect, or were actively counterproductive.

The Stuxnet worm aimed at Iran’s nuclear facilities is now believed to have delayed production of uranium by a few months at best, while accelerating the development of Iranian offensive cyber capabilities. The Sony Pictures hack by North Korea didn’t prevent the film it was designed to stop from being released.

In 2015 and 2016, Russia hit Ukraine with some of the most aggressive cyber attacks in history, directly targeting the Ukrainian power grid.

According to cybersecurity researcher Lennart Maschmeyer, the second of these attacks took 31 months to prepare, but only produced a 75-minute outage in some parts of Kyiv, a city accustomed to frequent power cuts.

“Most people will not even have registered that this was something out of the ordinary,” he said recently, adding that it also failed to achieve the objective of making Ukraine bend to Russia’s will, with consequences we see today.

What makes the difference between a disaster and a passing annoyance? Very often, says Ms Taylor, it’s the response of the defenders – which means all of us.

“Having a plan helps, it really does,” she says. “Thinking, ‘If we were denied access to our premises, what would we do? If we couldn’t use that service, what would we do?’

“We were on a BA flight a few weeks ago and they didn’t have access to any of their computer systems, so they did the whole flight on paper.

Those are the sorts of plans that really help in an emergency.”