There is never a good time to visit the migrant camp in Grande-Synthe, but now it looks particularly grim.

The mud is so deep that I see a man’s foot disappear up to his ankle as he comes to charge his mobile phone. A puddle has turned into a lake, straddling the width of the road that runs through the camp.

And as I chat to some of the people living here, they feed a brazier with both wood and hand gel to keep it burning.

It is a sorry, squalid and dangerous place, but it has a purpose. This is the staging post for people preparing to get to Britain.

Come to this camp and you can find a smuggler prepared to sell you passage across the Channel; someone who will tell you that, for a price, they can fulfil your dream of getting to the English shore.

A year on from the deaths of 31 people on a lightweight dinghy in the middle of the Channel, the appetite to make this crossing seems undiminished.

We meet Ahmed, who has already tried to get across the Channel and is determined to have another go soon. On his phone is the evidence – a map showing that he was nearly in English territorial waters when the engine on his boat had failed.

If he had just kept going a little further, then his rescuers would have taken him to Kent, rather than back to Northern France.

Then there’s Rebaz, who has spent months trekking here from Kurdistan. He has made the long, arduous journey despite the fact that the bottom half of his left leg has been amputated. He says it was ripped away when he was near an airstrike in Iraq.

Rebaz blames NATO for the injury, but is still determined to get to Britain because “life is better there – and I am going for the sake of the future of my children.”

When I ask him if he worries about the danger, or the spectre of people dying in the Channel, he shrugs and looks genuinely indifferent. “I am not scared,” he tells me. “Nobody here is scared. I have to go – I have no other option.”

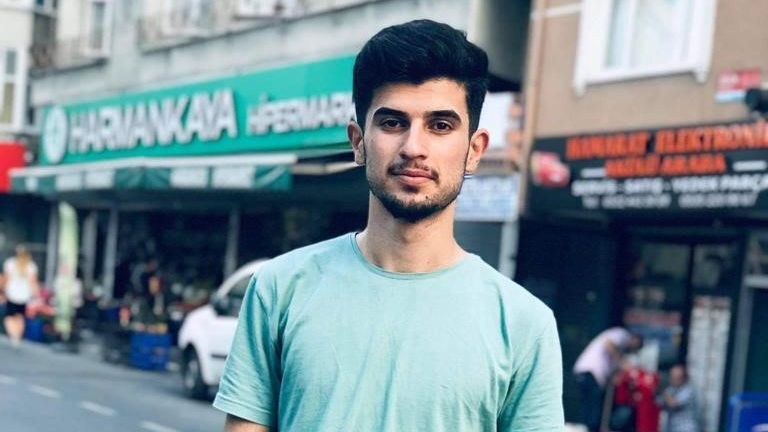

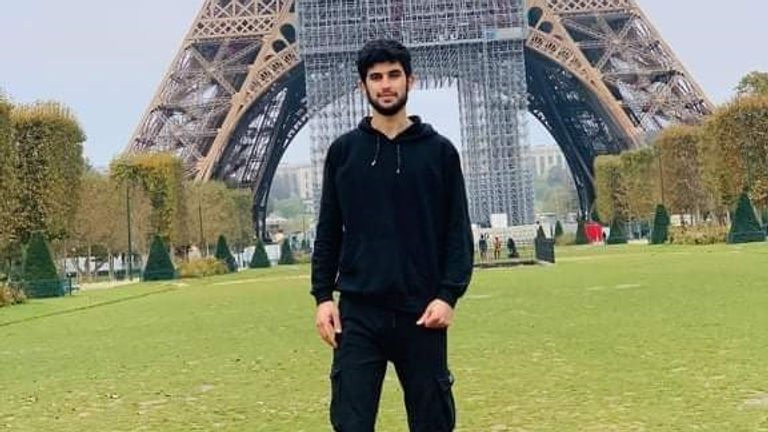

It was that drive that propelled 33 people to get on that ill-fated boat a year ago, when so many perished and only two survived. Four bodies have never been recovered, including that of Twana Mamand Mohammad, who was 18.

A keen athlete, who enjoyed Taekwondo and football, he had always wanted to leave Iraq, see Europe and hopefully become a footballer in the Premier League.

His brother, Zana, described him as “no trouble – at home, in the street, at school, in his school teams and among his friends”. He was, he said, “the go-to person in the family”.

On the night he died, Twana had previously messaged his anxious brother to reassure him that all was okay, saying the boat was working fine and that they were on their way to Britain.

Instead, a little later the engine failed. Sky News has seen transcripts of phone and text conversations between people on the boat and French emergency services, and they paint a picture of chaos at sea, allied to hesitation and indifference on the land.

Those on the boat called the French emergency service line, but help was not sent.

Then they were told that they were, in fact, in British coastal waters, so should phone the UK authorities. They, in turn, said the boat was in French waters.

And so it went on until, hours later, with the buck being passed and information not being passed between the two authorities. The boat took on water but when the French were told this, the reply was that it was “English water”.

Click to subscribe to the Sky News Daily wherever you get your podcasts

Eventually, awfully, the passengers went into the sea, hours after phoning to ask for assistance that never came.

Instead, it fell to a fishing boat to raise the alarm after spotting bodies in the water.

Zana is now in France, trying to find out more about the circumstances surrounding his brother’s death. He remains shattered by the tragedy and bewildered that desperate people could have been left without help.

“Because this incident happened in the waters between both countries our loved ones contacted both countries and requested assistance,” he says. “But none of them offered assistance.”

Read more:

English Channel deaths: Government has ‘learned nothing’ since 31 people died in tragedy

Immigration minister Robert Jenrick ‘should resign’ over migrant hotels, Tory MP says

He says that he now tells people not to follow in his brother’s footsteps; to avoid this perilous crossing and think about their safety. And his advice, he says, is ignored.

“Whoever you tell not to embark on this boat journey, they say ‘Whatever God has in store for us – that will happen’.

“So I tell them the tragic journey of Twana but this migration continues. And it will continue.”

And he’s right. The number of people crossing the Channel has increased over the past year. Since the disaster in November 2021, around 44,000 people have arrived in Britain using a small boat.

It is evening in Dunkirk and a procession winds its way through the town – a memorial march to remember the 31 people who died.

It ends on the beach, where the names of the victims are read out and hand-painted signs, embossed with their names, are held up. Twana’s name is there, along with everyone else – a catalogue of mainly young lives cut short in the most harrowing of circumstances.

At the time, it seemed like the sort of tragedy that would demand change. But in reality, the boats are still leaving, the smugglers are still cashing in, and the camps are still buzzing with people.

And as long as desperate people continue to cross the world’s busiest shipping lane in feeble, flimsy craft, the prospect of another disaster seems, grimly, inevitable.