During the post-war building boom of the 1950s, 60s and 70s, reinforced aerated autoclaved concrete (RAAC) was something of a wonder material.

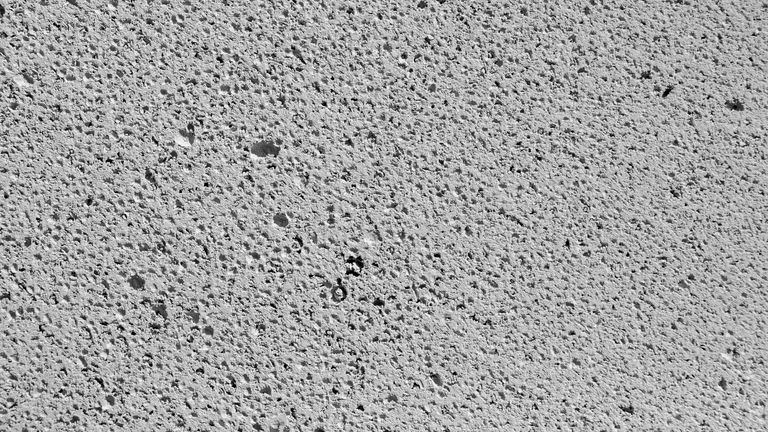

Filled with bubbles of air, the material is about a quarter of the weight of normal reinforced concrete.

RAAC was seen as ideal for shaping into lighter, pre-formed concrete components used in the modern lego-like construction of many public buildings of the time.

Given its light weight, planks of RAAC were widely used to make the flat roofs – a key reason why the current situation is so dangerous.

In the 1990s, when the material was still being used, structural engineers discovered that the strength of RAAC wasn’t standing the test of time.

The porous, sponge-like concrete – especially when used on roofs – could easily absorb moisture, weakening the material and also corroding steel reinforcement within.

As it weakened, it sagged, leading to water pooling on roofs, exacerbating the problem.

RAAC made in the 1950s was at risk of failure by the 1980s, the report concluded.

About 30 years ago, it became known that the lifespan of RAAC in many of public buildings, including hospitals and schools was no greater than 30 years.

Yet it seems, not much happened.

Read more:

School buildings forced to close over concrete safety fears

School building collapse that causes death or injury ‘very likely’

Until 2018 when the roof of a primary school in Gravesend, Kent suddenly collapsed. Thankfully, it happened on a weekend and no one was injured.

The investigation into the collapse revealed the RAAC planks used in the roof had weakened with age. But also steel reinforcement inside it didn’t extend all the way to the ends where it was supported by the walls.

Not only was there a problem with the material, there were problems with construction too.

In government, work began to find out which schools (and separately, hospitals) were at structural risk due to RAAC.

Thankfully, the 104 schools we now know are at the greatest risk are only a small fraction of the 22,000 state-owned nurseries, primaries, secondaries and colleges in England.

It’s going to be a chaotic start to the academic year for teachers and pupils in those schools.

And it’s no surprise that many are wondering about chaos in the Department for Education.

This is a problem for which urgent action has been long overdue, yet the decision to take it has come at possibly the most disruptive time possible.