The Black Death had such an impact on the human immune system that it still shapes how our bodies tackle today’s diseases, a study has found.

By analysing centuries-old DNA from victims and survivors of the devastating pandemic, which is estimated to have killed upwards of 200 million people between 1346 and 1353, scientists identified key genetic differences that determined who lived and who died.

Those aspects of our immune system have continued to evolve, and genes which once helped protect against the Black Death – the most fatal plague in human history – are today associated with susceptibility to diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s.

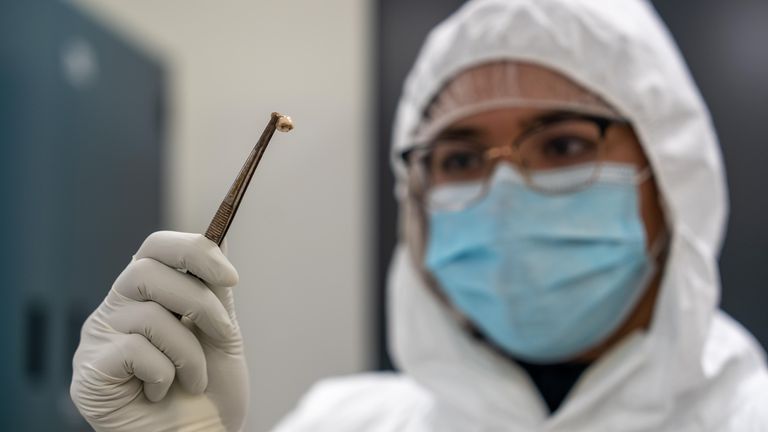

More than 500 DNA samples from victims and survivors – mostly in London – spanning a 100-year window before, during and after the pandemic, were examined by the researchers.

Among them were people who had been buried in the capital’s East Smithfield plague pits in 1348 and 1349, which were used for mass burials similar to those seen in some countries during the worst of COVID-19.

“This was a very direct way to evaluate the impact that a single pathogen had on human evolution,” said the study’s co-senior author Dr Luis Barreiro.

The geneticist added: “This is – to my knowledge – the first demonstration that the Black Death was an important selective pressure to the evolution of the human immune system.”

How was the study carried out?

The scientists, from McMaster University, the University of Chicago, the Pasteur Institute, and others, searched for signs of genetic adaptation related to the plague.

They identified four genes that were under selection, all involved in the production of proteins which defend our systems from invading pathogens.

Versions of those genes, called alleles, either protected or rendered one susceptible to the plague.

Those with two identical copies of a particular gene, ERAP2, survived at much higher rates than those with the opposing set of copies, as they allowed for more efficient neutralisation of the bacterium.

What did those genes mean for death rates?

The bacterium which caused the plague, named yersinia pestis, was new to Europe when it arrived and most were extremely vulnerable.

It killed upwards of 50% of people who lived in some of the most densely populated places in the world.

During future waves over subsequent centuries, death rates decreased as immune systems became used to dealing with the disease – as we have started to see with COVID-19.

Those who had the identical copies of ERAP2 were 40-50% more likely to survive, researchers say.

So why does this matter to current diseases?

The Black Death was so impactful that it shaped the very nature of the human immune system – had it not adapted, even more people would have died.

But what was once a protective gene against plague in the Middle Ages is today associated with increased susceptibility to autoimmune diseases, the seven-year study has found.

The team describes it as a balancing act which evolution plays with the human genome.

“Diseases and epidemics like the Black Death leave impacts on our genomes, like archaeology projects to detect,” explained senior co-author Professor Hendrik Poinar

“This is a first look at how pandemics can modify our genomes but go undetected in modern populations.

“These genes are under-balancing selection – what provided tremendous protection during hundreds of years of plague epidemics has turned out to be autoimmune related now. A hyperactive immune system may have been great in the past, but in the environment today it might not be as helpful.”

The full findings have been published in the journal Nature.

For more on science and technology, explore the future with Sky News at Big Ideas Live 2022.

Find out more and book tickets here