Digital technology has been used to rebuild the brain of Thecodontosaurus, giving new insights into one of the earliest dinosaurs to roam the planet.

Better known as the Bristol dinosaur after its fossils were found in the city in the 1830s, it was only the fourth dinosaur to be named.

Research now suggests it may have eaten meat and moved fast on two legs – after palaeontologists used 3D modelling and advanced imaging of fossils to reconstruct its brain.

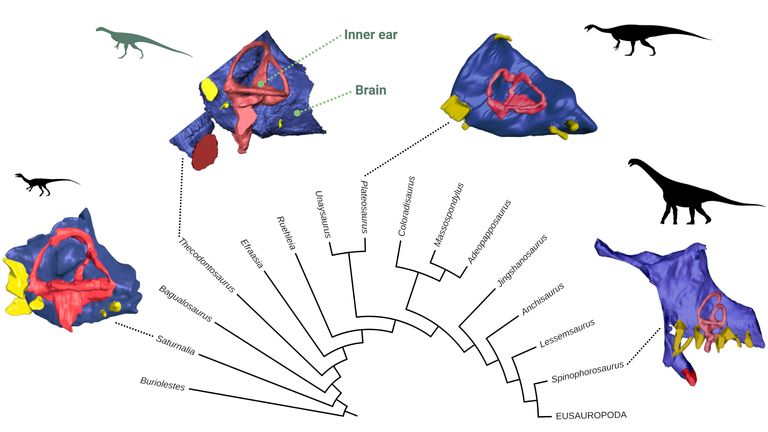

They concluded the small dinosaur was possibly carnivorous, unlike its giant long-necked later relatives Diplodocus and Brontosaurus, which only fed on plants.

Antonio Ballell, lead author of the University of Bristol study, said: “Our analysis of Thecodontosaurus’ brain uncovered many fascinating features, some of which were quite surprising.

“Whereas its later relatives moved around ponderously on all fours, our findings suggest this species may have walked on two legs and been occasionally carnivorous.”

Thecodontosaurus lived in the late Triassic age around 205 million years ago and was the size of a large dog.

While its fossils were discovered nearly 200 years ago, many of which are preserved at the University of Bristol, scientists have only very recently been able to use technology to extract new information without destroying them.

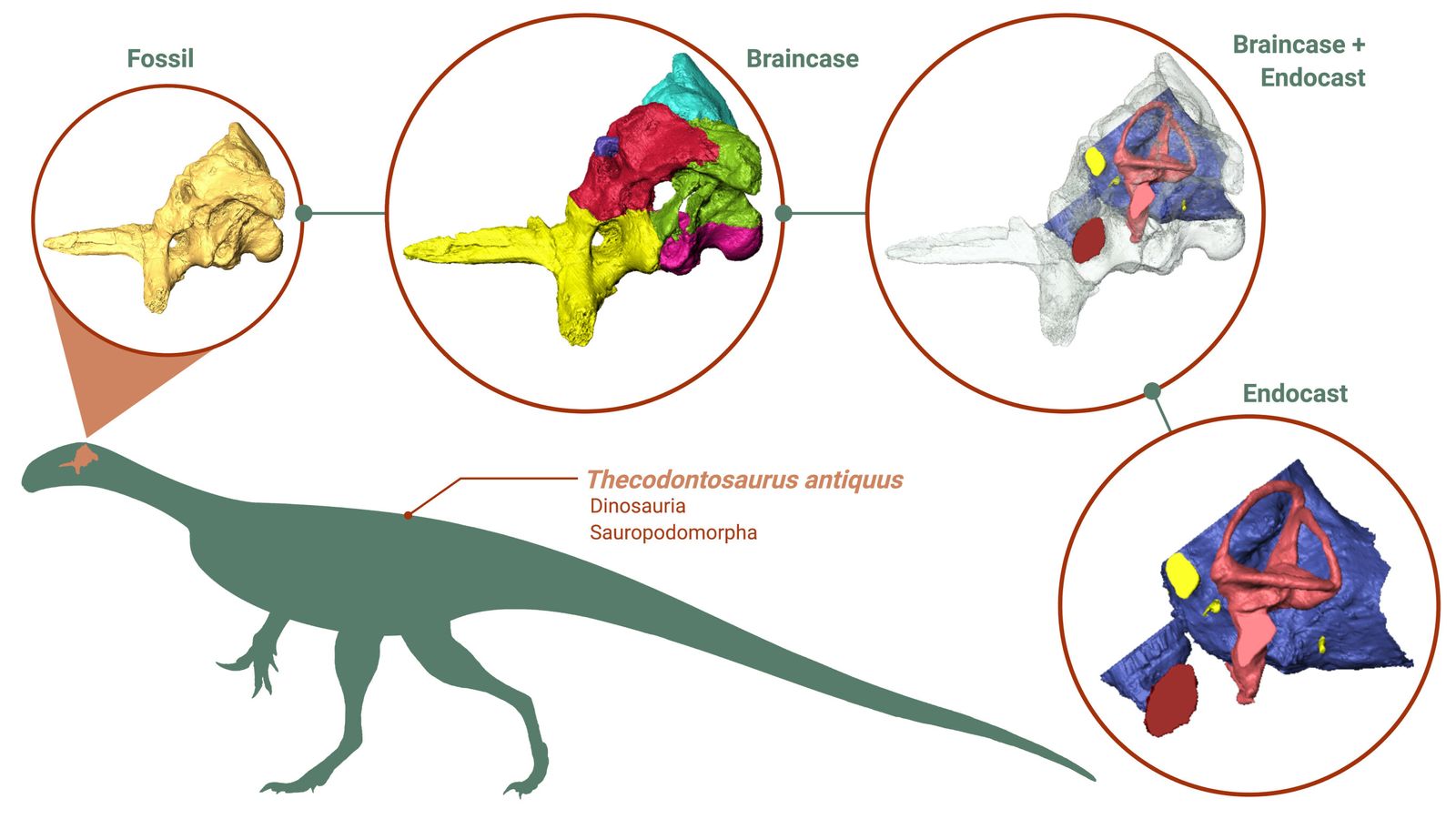

3D models were generated from CT scans by digitally extracting the bone from the rock, identifying anatomical details about its brain and inner ear previously unseen in the fossil.

“Even though the actual brain is long gone, the software allows us to recreate brain and inner ear shape via the dimensions of the cavities left behind,” Mr Ballell said.

“Its brain cast even showed the detail of the floccular lobes, located at the back of the brain, which are important for balance.

“This structure is also associated with the control of balance and eye and neck movements, suggesting Thecodontosaurus was relatively agile and could keep a stable gaze while moving fast.”

Mr Ballell, a PhD student at the university’s School of Earth Sciences, said analysis showed parts of the brain associated with keeping the head and eyes steady during movement were well-developed.

“This could also mean Thecodontosaurus could occasionally catch prey, although its tooth morphology suggests plants were the main component of its diet. It’s possible it adopted omnivorous habits,” he said.

The researchers were also able to reconstruct the inner ears, allowing them estimate that its hearing frequency was relatively high, pointing towards some sort of social complexity – meaning it had an ability to recognise varied squeaks and honks from different animals.

Professor Mike Benton, the study’s co-author, said: “It’s great to see how new technologies are allowing us to find out even more about how this little dinosaur lived more than 200 million years ago.”

The research is published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.