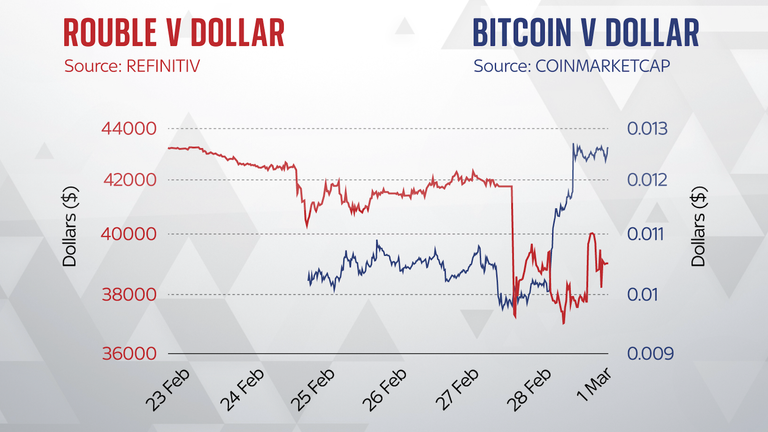

Sanctions imposed on Russia for invading Ukraine caused the rouble to plummet on Monday but as it dropped the value of cryptocurrencies including Bitcoin and Ethereum shot up.

Unlike the global financial system where central authorities can prevent Vladimir Putin’s regime from accessing the Kremlin’s foreign reserves, and Russian banks from using the SWIFT payments network, there are no technical means to block Russia and its oligarchs trading cryptocurrencies.

That doesn’t mean that unregulated cryptocurrencies provide a loophole for the country’s institutions and oligarchs, just that the enforcement mechanisms used by financial institutions to monitor transactions aren’t always available. Laws requiring cryptocurrency exchanges to verify their customers’ identities still apply in all jurisdictions where the sanctions have been issued.

Russians ‘have city surrounded’ – latest updates on the Ukraine invasion

Caroline Malcolm, the head of international public policy for Chainalysis, said: “As with the traditional financial system, Russia can leverage cryptocurrency to evade the sanctions that are being put in place in response to their invasion of Ukraine. And as in the traditional financial system, the cryptocurrency ecosystem can put measures in place to identify transactions from identified sanctioned entities.”

Cryptocurrency not ideal for the ultra-rich

But for the volumes of trading that Russia would need to weather the sanctions covering $643bn in international reserves, there simply isn’t enough cryptocurrency available – and the volumes would be impossible to transfer covertly as the blockchain is, by design, a public ledger of all transactions.

Instead, as the country faces potential hyperinflation, the rise for Bitcoin and Ethereum is more likely to be caused by Russian citizens (rather than the government and oligarchs) looking to move their roubles into other currencies, or very possibly due to speculation from others about Russians doing so.

“It is unlikely that designated persons would move around large quantities of crypto now,” Ms Malcom said. “Russia’s elite and financial authorities have been preparing for sanctions for some time.”

Chainalysis, which is a blockchain-forensics business, identified a rise in rouble and Ukrainian hryvnia trading volume ahead of the currency dropping.

“To the extent that cryptocurrency may be used to evade sanctions related to this crisis, it likely would have happened slowly over the past several months. And all of these transactions would be recorded on the blockchain, permanently,” she added, meaning that they could be detected for enforcement purposes.

The dangers of a pariah state

Sanctions on North Korea for its nuclear weapons tests have led to Pyonyang turning to cyber crime to fund its nuclear and ballistic missile programmes. The weakness of the North Korean economy has spurred the country’s government to allegedly sponsor a wide range of international criminal activities, including currency counterfeiting and manufacturing drugs.

While the sanctions on Russia will not bring the country into comparable economic circumstances, it has benefited from decades of integration with the global financial system and the economic damage caused by the sanctions could create the room for an even more tolerant attitude towards cyber crime.

The global cyber underworld has a significant nexus to Russia for a range of reasons, including the country’s legal system, which doesn’t allow the security services to arrest citizens for crimes committed abroad; corruption; and the alleged collusion of the country’s intelligence agencies both inside Russia and in neighbouring counties, including Ukraine.

According to Chainalysis, 74% of global ransomware revenues last year went to Russian-affiliated entities. Cyber security researchers have regularly reported how the malware developed by these groups is designed to avoid affecting computer networks using the Russian language, indicating the developers’ potential exposure to Russian law enforcement.

Cyber criminals declare support for Russia

Collusion between the Russian state and cyber criminals has been repeatedly alleged by Western law enforcement, including the case of Maksim Yakubets, who was accused of acquiring “confidential documents” for the FSB, Russia’s federal security service, while hacking computers to commit bank fraud.

But last week one of the most active ransomware groups explicitly announced its “full support” for the Russian government. Perhaps it was a moment of patriotic fervour, or the group had felt pressure from the Kremlin, but this gang, known as Conti, warned: “If anybody will decide to organise a cyber attack or any war activities against Russia, we are going to use… all possible resources to strike back at the critical infrastructures of an enemy.”

A later statement attempted to retract the criminal group’s explicit support for the Kremlin, clarifying it was “a response to Western warmongering” and explaining: “We do not ally with any government and we condemn the ongoing war. However, since the West is known to wage its wars primarily by targeting civilians, we will use our resources in order to strike back.”

Read more:

Cyber, war and Ukraine – What does recent history teach us to expect?

Others declare support for Ukraine

But the damage was done. It resulted in a range of activist and potentially criminal groups declaring their support for Ukraine, and – more significantly – it led to an apparently disgruntled Conti insider taking umbrage with their former colleagues’ support for the Russian invasion and responding by leaking internal chat logs, signing off their message with: “Glory to Ukraine!”

The leaker shared a cache of thousands of internal chat logs detailing the ransomware group’s activities. The leaks suggest the Conti gang members even targeted Bellingcat researchers investigating the poisoning of prominent Putin critic Alexey Navalny, indicating to those researchers an affiliation with the Russian state.

Among the other details in the leaks were the gang’s cryptocurrency addresses which – by today’s cumulative valuation, certainly much higher than the value of these transactions at the time they occurred – show the gang brought in more than $2.7bn in Bitcoin since 2017.

Even this though is just a fraction of the $74bn that cyber security company Emsisoft estimates was demanded by ransomware criminals last year alone. The company stressed that its figure was based on limited information and was intended to highlight the scale of the problem rather than offer an accurate estimate of the true global cost.

Brett Callow, a senior threat analyst at Emsisoft, told Sky News: “What impact sanctions and other aspects of the war will have in relation to financially motivated cyber crime in unclear. It could be that we’ll see a spike as Russia looks for ways to increase its revenues.”

Referring to the disruption caused to the Conti gang, he added: “On the other hand, the fact that there is considerable crossover between Russian and Ukrainian cyber crime groups could complicate their operations due to increasing tensions and actually result in a temporary decrease in activity.”