Three vaccines approved for use in the UK have all reported they are around 90% effective in late stage trials.

The UK was the first country in the world to approve the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

It is currently being rolled out across the nation, alongside the University of Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine, which was given the green light by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) weeks later and administered to patients from the start of this year.

Approval of the Moderna jab followed, but it will likely not become available until March. This is because it is being manufactured in the US at first, and will take a few months before facilities in Europe will be ready to distribute.

A fourth COVID-19 vaccine – the Novavax jab – is being assessed by the MHRA and could be approved for use in the UK within weeks.

A fifth, also pending UK approval, has been developed by Johnson & Johnson. The fact it only needs one dose, unlike the others which require two doses several weeks apart, could help to speed up vaccinations.

The government previously issued guidance on the vaccines requiring two doses, saying the “preferred” option was to offer both doses from the same supplier but that it would be “reasonable” to receive a second dose from another.

However, Dr Mary Ramsay, head of immunisations at Public Health England (PHE), told Sky News she did not recommend mixing COVID-19 vaccines, but said “it is better to give a second dose of another vaccine than not at all”.

Before comparing vaccines, it is important to be aware all trials use different criteria for what counts as an infection which can lead to variations in results for effectiveness. However, all of the vaccines will reduce hospitalisations and deaths.

Using a virus that causes the common cold in chimpanzees as a Trojan horse, Oxford adapted their existing vaccine technology to target COVID-19.

It had already been modified so it didn’t cause disease in humans. But they added in one of the genes from the new coronavirus.

The Oxford vaccine smuggles the coronavirus gene into human cells to make the spike protein – the unique signature of COVID-19 – which the immune system builds up a response to if the real virus enters the body.

Both the Pfizer and Moderna jabs use technology known as mRNA, which introduces into the body a messenger sequence that contains the genetic instructions for the vaccinated person’s own cells to produce the antigens and generate an immune response. Using mRNA in this way is a new method.

The Novavax jab is a new kind of vaccine – instead of injecting the genetic material for the spike protein, this is the protein itself.

It combines an engineered protein from the virus that causes COVID-19 with a plant-based ingredient to help generate a stronger immune response. If the body encounters coronavirus in the future, the body is primed to fend it off.

The Johnson and Johnson jab uses similar technology to the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine – harnessing a virus to act as a Trojan horse that sneaks some of the genetic blueprint for the coronavirus into the body.

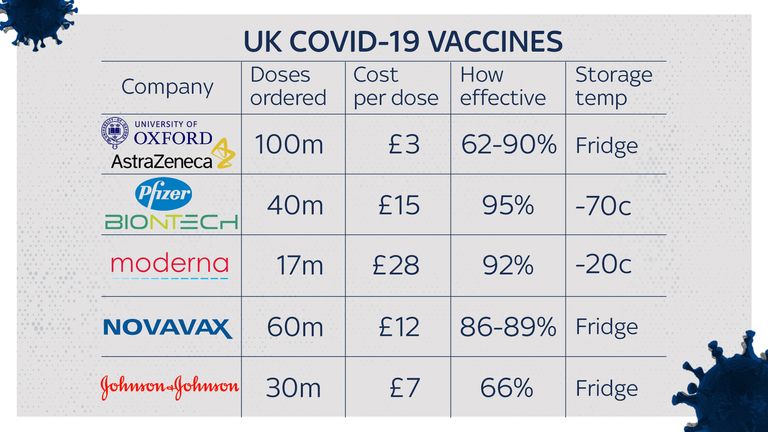

Final data from the Pfizer vaccine found it offers 95% protection against the virus after two doses.

It also proved 94% effective among adults over the age of 65 – who are generally more vulnerable.

The first dose provided 52% protection after 12 days.

Moderna’s results indicate 94.5% effectiveness but it said the trials are ongoing and the final number could change.

The Oxford trial found with two doses its vaccine was 62% effective, but when people were given a half dose followed by a full dose at least a month later its efficacy reportedly rose to 90%.

Some questioned these results – including the UK medicines regulator, which reviewed the data and recommended that two full doses should be administered.

The agency concluded that the Oxford vaccine was up to 80% effective when the second dose was delayed by three months.

The jab already provides 70% protection 22 days after the first dose, according to the UK’s Joint Committee of Vaccinations and Immunisations (JCVI), which advises the government.

The second dose for both the Pfizer and Oxford vaccines can be taken up to 12 weeks after the first.

When it was initially approved, the UK medicines regulator said the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine should be administered 21 days after the first – but changed this to a longer interval of between 21 days and 12 weeks.

For the Oxford vaccine, the second dose should be taken between four and 12 weeks after the first.

Subscribe to the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

Professor Wei Shen Lim, chair of the Joint Committee of Vaccinations and Immunisations, said delaying the second dose would allow the NHS to prioritise the delivery of the first dose to as many people as possible.

Those who are pregnant or breastfeeding can take any of the vaccines approved in the UK, but a discussion with a doctor about the risks and benefits is recommended.

Anyone with an allergy to a specific ingredient in the Pfizer or Oxford vaccines should not receive the jabs.

People with other types of allergies can now safely take the vaccines, according to the UK medicines regulator, which has looked at evidence from hundreds of thousands of people inoculated so far.

Extensive late-stage trials of the Novavax vaccine, called NVX-CoV2373 and which also requires two doses, suggest it is 89% effective in preventing coronavirus.

It offers 86% protection against the new British strain of COVID-19, which is up to 70% more transmissible.

A smaller, separate trial shows it to be about 60% effective against the South African variant, despite concerns that this strain may not respond to vaccines.

The biggest difference between the vaccine developed by Janssen, a Belgian pharmaceutical company owned by Johnson & Johnson, and the others is it is a single-shot vaccine.

It has been found to be up to 85% effective in preventing the most serious coronavirus symptoms, and 66% effective at preventing moderate to severe illness.

One of the main differences between the vaccines is how they need to be stored.

The Oxford, Moderna, Novavax and Johnson & Johnson vaccines are much easier to distribute than the Pfizer jab.

During shipment and storage, the Pfizer vaccine must be kept at around -70C (-100F) to maintain optimal efficacy and it also has to be mixed with another liquid before it can be administered.

Pfizer has developed its own packaging to keep doses cold with dry ice so they can be stored for 10 days without specialised freezers, but doses still have to be flown from Belgium then sent to vaccination centres in trucks with thermo sensors and GPS trackers.

The Moderna vaccine has been shown to last for up to 30 days in household fridges, at room temperature for up to 12 hours, and remains stable at -20C (-4F) – equal to most household or medical freezers – for up to six months.

The company claims mRNA-1273 can be distributed using widely available vaccine delivery and storage infrastructure – with no dilution required prior to vaccination.

Like most other vaccines, the Oxford one needs to be sent to vaccination centres in refrigerated vans or cool boxes and stored in a special vaccine fridge between 2C (36F) and 8C (46F), and protected from light.

Both the Novavax and J&J vaccines also only need to be stored at fridge temperatures, making their storage, distribution and handling much easier.

Each vaccine’s price tags vary widely, although the vaccine rollout is being paid for by the government so the jabs will be free for those using the NHS.

The Moderna vaccine is very expensive. It was pitched for $38 (£28) a dose during the summer – much higher than Pfizer, at $20 (£15).

The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is much cheaper, with the company saying it will cost the government “the same as a cup of coffee”. Sky News understands it will cost a little under £3 per dose, with two doses needed.

AstraZeneca said it will not sell its jab for a profit so it is available to all countries, no matter the size of their economy.

Moderna – a commercial company – has an interest in making profits, while the researchers for Pfizer made sure it will be made not-for-profit as long as the pandemic continues.

Dr Zoltan Kis, research associate at the Future Vaccine Manufacturing Hub, Imperial College London, said the Moderna vaccine’s higher mRNA amount per dose (100 micrograms) compared with Pfizer’s (30 micrograms) meant the latter could be produced in higher numbers and at lower cost.

He added that transport issues with Pfizer may counteract that initial advantage, and pointed to the higher temperature at which the Moderna candidate could be stored.

“Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine can be distributed substantially easier and at lower costs compared to the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine,” he said.

The Novavax jab comes at a cost of $16 (£11.66) per vaccination, while the J&J vaccine costs around $10 a dose (£7.28) – so they are more expensive than the AstraZeneca vaccine, but cheaper than both Pfizer and Moderna treatments.

The UK government has secured around 40 million doses of the Pfizer vaccine – enough for 20 million people or about a third of the UK population – and it has reserved 100 million doses of the Oxford vaccine, which it has helped fund.

Britain has ordered five million doses of the Moderna vaccine, to be delivered by spring. Health Secretary Matt Hancock said this candidate would not be available anywhere in Europe until then.

Moderna’s first target is the US market since it has been developed with the help of the federally funded National Institutes of Health and the US Department of Health and Human Services, so could be even more expensive for the UK.

It has also received $2.4bn (£1.8bn) in funding from the US government and plans to have 20 million doses available for use in the US by the end of the year – meaning other countries must form an orderly queue.

The UK has so far ordered 60 million doses of the Novavax vaccine, which are going to be manufactured in Stockton-on-Tees in County Durham. If approved, it would start to be rolled out in the second half of 2021.

Thirty million doses of the J&J vaccine have been ordered by the UK government, pending approval by the MHRA, with only one single injection required.