Reia DaCosta was told that having a child would kill her.

She was born with sickle cell disease, something that affects an estimated 15,000 people in the UK – the vast majority of whom have an African or Caribbean family background.

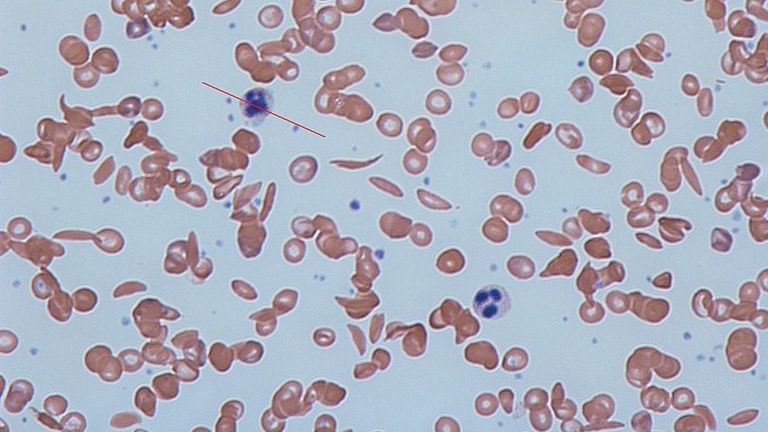

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a term describing a group of hereditary blood disorders affecting the oxygen-carrying protein used by red blood cells. People who have it produce abnormal sickle-shaped cells, which is where the disease gets its name from.

These crescent-shaped cells can carry less oxygen and because of their shape and rigidity they can also get stuck in small blood vessels causing excruciatingly painful episodes known as a sickle cell crisis.

“I had my first crisis at the age of about four, five where my mum literally just realised my body was just completely swollen,” recalled Reia, but other than that her younger years were “pretty great”.

However as she got older the disease started to affect her a lot worse, starting with her pregnancy.

“I had my daughter at 18 years old, and that was it, my body just went from bad to worse. I think [due to] juggling adult life and stuff like that,” said Reia.

“I was told that I could never have kids because it will kill me. We got told when I was younger that you [people with SCD] wouldn’t live past 40.”

“For me to have a child at that age, I was absolutely terrified. But then, the fact that I could do it was amazing,” she said.

Reia has been working since she was 16 but found the disease has forced her to work harder than others because it has made her take time off.

“Progressing my career into a management career has been 10 times harder because I have to try and keep up with the normal everyday person.

“With sickle cell you suffer from a lot of fatigue, so I am chronically fatigued. So, sleep is like gold to me, if I do not get sleep, I cannot function. Even if I have a good six hours sleep, I’m still fatigued, so I have to make sure that I’m on top of myself consistently,” she said.

“Being a working mother, that alone for a normal person is a lot, so for me to have sickle cell on top of that, it’s literally like Russian roulette, because the whole week can be great and then kapow, we can have a sick day, and I’m out for like four days.

“That affects my daughter, that affects the child care for my daughter, that affects my work life, and obviously it affects my body because I’m fully disabled, I cannot walk sometimes in my crisis. Sometimes I can’t breathe because my ribs are completely inflamed.

“I think the worst of it has been my back where I’ve been in hospital for like eight weeks because I physically cannot walk, and being at the age that I am 28 – who wants to use a commode at that age, you know what I mean?

“So, these are the things how it affects me the most, like when I go hospital, everybody around me is affected. My mother, her father, everyone’s got to change their whole life to fit me while I’m out, and there’s no warning sign, so I could literally be great today and by the end of today, you could hear that I’m in hospital.”

Reia said that for people with sickle cell disease, visits to A&E are challenging, even in the middle of a sickle cell crisis, as there is no priority for them to receive a bed.

The healthcare provisions available to patients with other diseases such as multiple sclerosis or diabetes – such as free prescriptions – aren’t available for people with SCD. Even though her prescriptions are available at NHS prices, she estimates she is still spending around £100 a month to manage her disease.

She said she feels as if it wasn’t looked at in the same bracket as those other diseases because it only affects African and Caribbean people: “I feel failed at times, but then I can’t just blame the system. It’s more of a global thing than just the NHS, but there are times that I’ve felt failed.”

Although hospitals can provide a month’s supply of medication without charge, sickle cell patients would need to keep attending every month to access this medication.

Reia says there have been petitions calling for SCD patients to be granted the same kind of exemptions given to those with other diseases: “We can’t heal it, and I live off folic acid and penicillin, every single day, let alone the pain drugs that need to be done to help me in my everyday life.”

“I’ve had to create my own self, and build my own self up and build my own mental health up to deal with my illness and just get on with it, because I’m not going to get babied for it,” said Reia.

“It’s never been recognised as a disability because one day I’m great and one day I’m bad and no one can ever understand that,” she added.

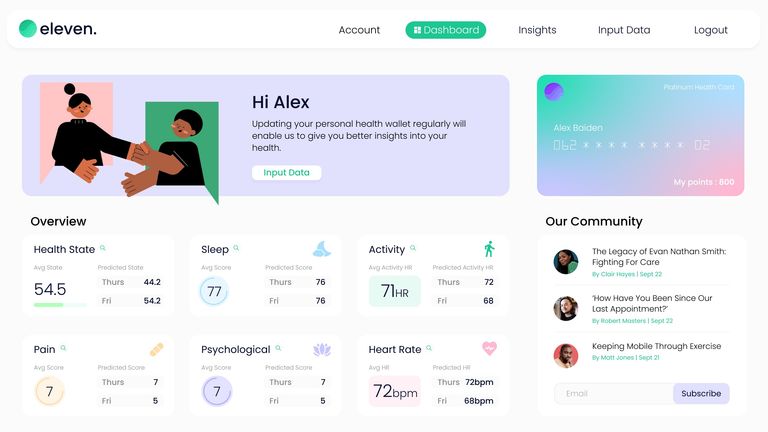

She was contacted by a British technology company called Eleven Health that was developing an online health monitoring platform and wanted patients from the sickle cell community to give them feedback.

Initially she was “really sceptical” as a result of her interactions with the health services: “When you have a disease and you don’t really get help, you’re kind of afraid to think, oh, is this really going to help me.”

Reia now works for Eleven Health, which is offering to enlist more SCD patients in its platform through various community groups. The company says it only shares the data with patient’s clinical teams and, in an aggregated form, with researchers.

During lockdown she was having a sickle cell crisis at home. As her daughter was being homeschooled she had childcare commitments which meant she couldn’t visit the hospital, but was attempting to manage the pain herself with oral morphine.

“Morphine has really bad side effects. The amount of morphine that I have to take, just to get my pain down is, is incredibly high compared to a normal person. What happens when you take a lot of morphine is you can also suffer from respiratory problems – too much of it can cause issues,” she said.

Using the wearable she tracked her blood oxygen levels and found they had dropped to 90%.

“It’s never got that low for me unless I’ve been extremely ill, and I was just like, ‘Okay, it’s time to call the ambulance’. I didn’t even think about how I was going to get childcare for my daughter. I just knew that it was time to go.”

When the ambulance crew arrived they confirmed the reading. Reia credits the wearable with saving her life.

She has also used the health dashboard and the data its accrued to try and make accurate predictions of when she is going to have a pain crisis and has discovered that her menstrual cycle is a big trigger.

“When you’re living day-to-day life, being a working mum, having a child, having this illness, being fatigued, these things completely slip your brain.

“So the wearable, and the whole platform has completely helped me change my whole lifestyle around, and it’s been a good couple of months… and now I can definitely say that I’m a lot more confident to handle my illness,” she added.

“Whatever disease you have, you’ve got to find your own pace in [dealing with] it anyway. So, when you have an illness like sickle cell – and it’s never been noticed on paper, it’s never been noticed as a disability, you just have to go on.

“Because you can’t just sit back home and cry about it and fail, you have to go on, you have to live your life, you have to find someone that loves you for your illness, you have to have kids, you have to work to earn your way through.

“So yeah, I feel like I have been failed at times but at least you’ve got platforms like this that can come in and kind of, restore that faith in myself and help feel great about me, so that actually I can take control of my health,” she said, adding that she hopes to have more children with her husband.