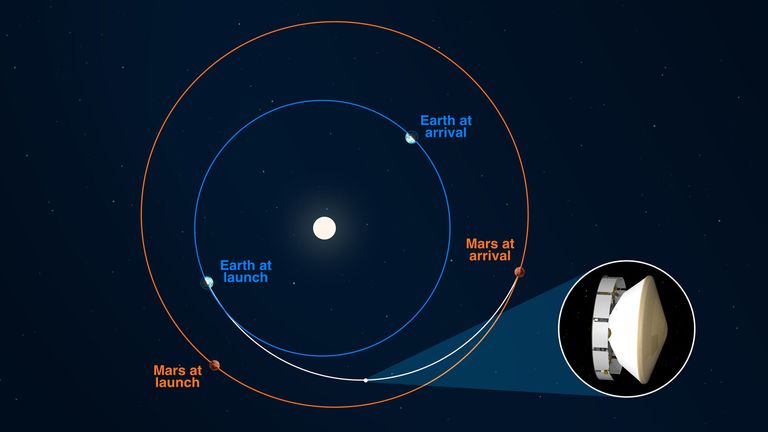

In just two days, NASA’s Perseverance rover will complete its seven-month journey to Mars and begin the shortest and by far the most intense stage of its mission: landing.

Live on Sky News at 7.15pm UK time on Thursday, and in a maximum of seven minutes (although it could take less if something goes wrong), the rover will enter the Martian atmosphere, descend through it, and ultimately land upon the surface.

One way or another, Perseverance will decelerate from nearly 20,000kmph (12,500mph) – fast enough to get from London to New York in 15 minutes – to being stationary on the planet’s surface.

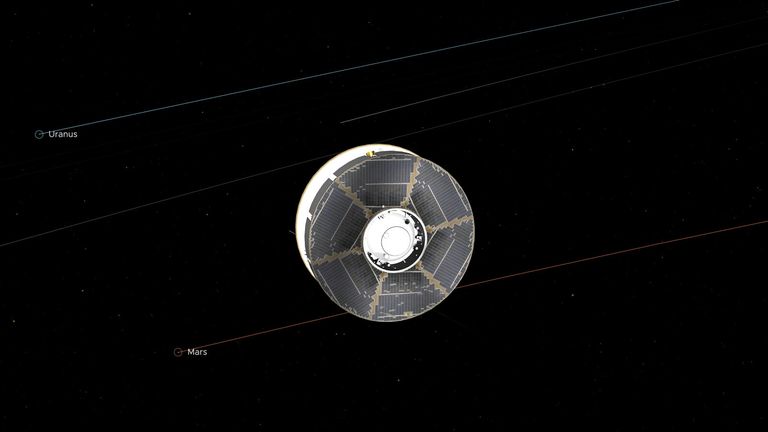

Excitingly, the mission carries more cameras with it than any other interplanetary mission in history – 19 of them, which will send back breathtaking images of the Martian landscape.

Four other cameras are attached to the parts of the spacecraft involved in entry, descent and landing, meaning engineers will be able to put together a high-definition view of the landing process, as well as allowing people at home for the first time ever to follow along live with raw and processed images.

Of course, radio transmissions from Mars take 10 minutes to reach Earth. By the time we see that Perseverance has entered the Martian atmosphere, it will have either already landed or been destroyed.

The rover, which has a mass of 1,050kg (2,313lbs), could easily end up adding to the craters on the planet’s surface. NASA hopes its brand new guidance and parachute-triggering technology will help steer the rover away from these hazards, but its controllers back on Earth will be helpless.

The last NASA spacecraft to land on Mars was the InSight robotic probe, which touched down on 26 November 2018. Although there was no live video, the landing was monitored through telemetry clocking the probe’s velocity.

Half of all missions to Mars have failed, with the entry, descent, and landing portion of the mission usually proving the most difficult.

The Soviet Union successfully made the first impact on Mars on 27 November 1971, although the spacecraft was destroyed, before then successfully soft landing a spacecraft there later that year – which functioned for less than two minutes.

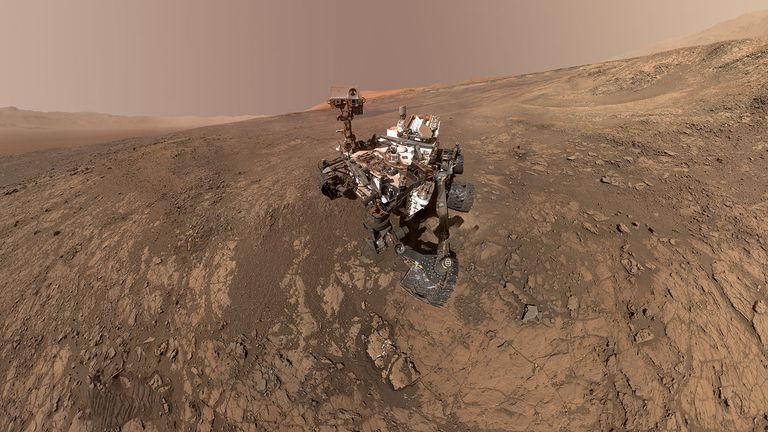

However, some missions prove unusually successful. NASA’s Curiosity rover landed on 6 August 2012 with an expectation that it would be able to complete a two-year mission.

As of today, the rover is still operational and its mission has been indefinitely extended. The design of the Curiosity rover serves as the basis for Perseverance, although the new rover carries different scientific instruments.

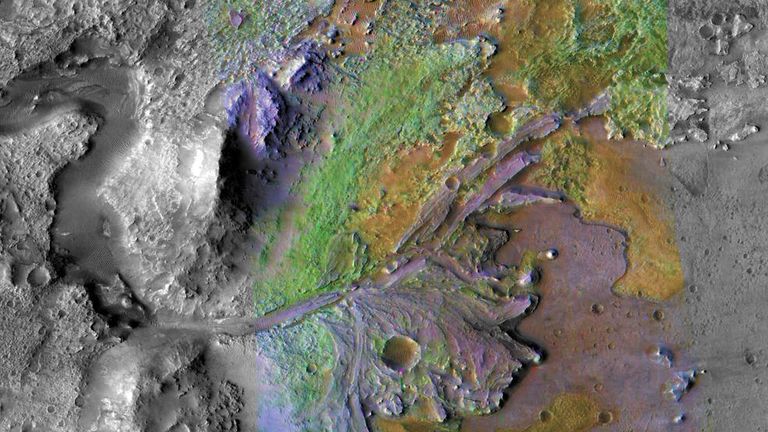

The Perseverance rover is intended to touch down in an ancient river delta and former lake on the Martian surface known as the Jezero Crater.

The Jezero Crater is full of obstacles and dangers to the rover, including boulders, cliffs, sand dunes and depressions, any one of which could end the mission, both in landing and as the rover drives along the surface.

The deposits in the crater are rich in clay minerals, which form in the presence of water, meaning life may have once existed there – and such sediments on Earth have been known to store microscopic fossils.

Scientists have also noted that the crater doesn’t have a depth which matches its diameter, which means sediment likely entered the crater through flowing water – potentially up to a kilometre of it.

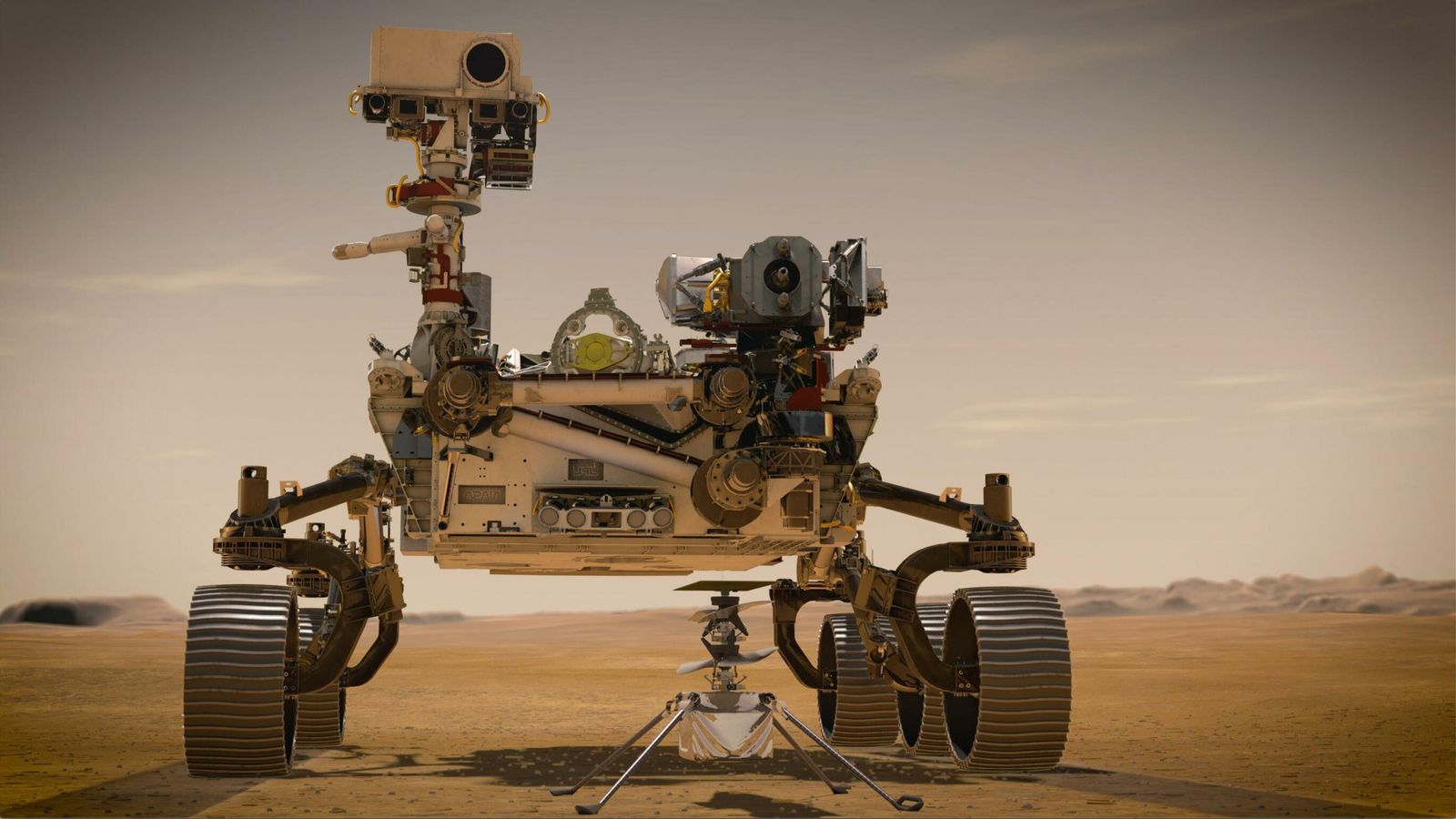

Perseverance is also equipped with a miniature helicopter named Ingenuity, which weighs just 4lb (1.8kg) and will be the first rotorcraft to fly on another planet, although that test mission isn’t due until a while after the landing.

“The laws of physics may say it’s near impossible to fly on Mars, but actually flying a heavier-than-air vehicle on the red planet is much harder than that,” NASA quipped.

The little chopper underwent a series of drills simulating the mission in a testing facility in California, including a high-vibration environment to mimic how it will hold up under the launch and landing conditions, and extreme temperature swings such as those experienced on Mars.

The autonomous test helicopter will have an on-board camera and will be powered by a solar panel, but will not contain any scientific instruments.

NASA aims to develop the drone as a prototype to see if it could be worth attaching scientific sensors to similar devices in future.