Science is a slog. Not a series of “Eureka!” moments.

It’s why I hate the word “breakthrough” when it comes to research discoveries.

But in the case of this new drug for Alzheimer’s that word is more than justified.

Not because lecanemab is a cure for the disease that is destroying the lives of hundreds of thousands of people in the UK at any one time. It isn’t.

It’s a breakthrough because it’s the first positive sign we’ve had that a decades-long slog to find a cure for Alzheimer’s is going to pay off.

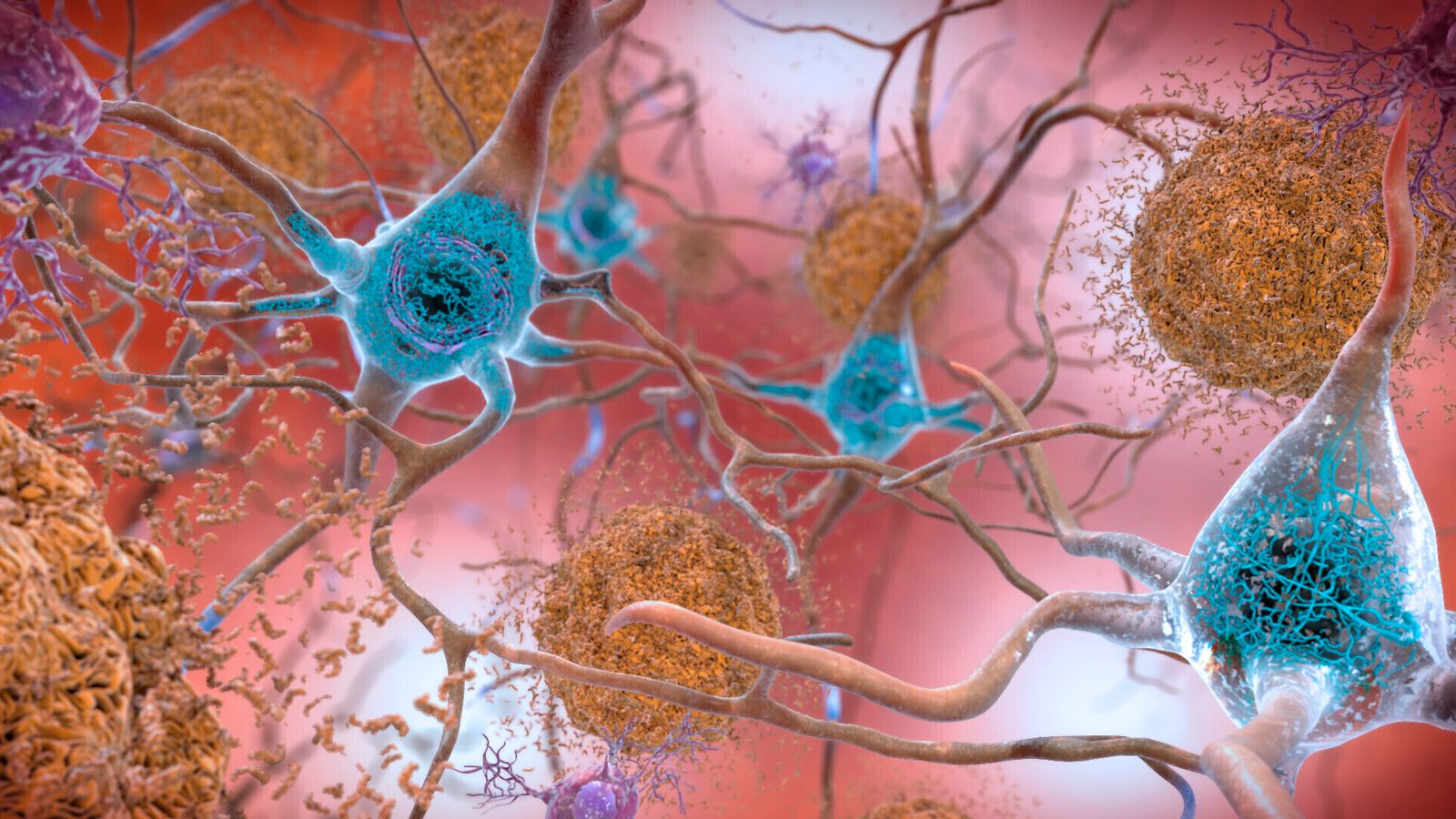

It all comes down to a rogue protein called amyloid that builds up in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. The protein is like molecular junk that clogs up and eventually kills brain cells.

Professor Sir John Hardy at University College London first demonstrated the genetic underpinnings of the process 30 years ago.

It led to a surge in research and investment by pharmaceutical companies into drugs that could clear up amyloid and remove it from brain cells.

Over the years, a number of treatments that worked in the laboratory went into clinical trials. Some were proven to be very effective at removing amyloid from peoples’ brains. But none showed any measurable impact on the symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

As failure followed failure, some researchers were beginning to wonder whether the “amyloid hypothesis” for the cause of Alzheimer’s was even correct. Major drug firms that had invested in drugs targeting amyloid began to grow disillusioned and scale back investment.

Urgent need to detect disease before symptoms show

Lecanemab looks like it will change all that. It doesn’t just show the amyloid hypotheses is probably correct – it also might explain why previous drugs haven’t been successful.

The clinical trials of lecanemab showed it cleared amyloid from people’s brains much faster than previous medicines. Given clinical trials usually only run for a year or two, some experts believe the fact that lecanemab worked quicker than others is why they were able to detect the small but measurable slowing of Alzheimer’s symptoms in the people who were given it.

This has two important implications. First, it means that as people stay on the drug for longer it’s possible its beneficial effects improve more with time.

But it also speaks to the importance of giving drugs like lecanemab to people before amyloid has led to widespread damage. While the trial showed the progression of Alzheimer’s disease was slightly slower in people on the drug, their symptoms still got worse. The theory is that the amyloid they had been living with has already caused damage, and the drug may not help reverse it.

That means there’s now an urgent need for better tests to detect Alzheimer’s before symptoms start to show so lecanemab, and the drugs that will surely follow, can be tested much earlier.

If this breakthrough reinvigorates efforts to find more anti-amyloid drugs, and better tests are developed in parallel, real treatments to fight this terrible disease might not be far away.