The last century’s space race was a competition between the world’s great powers and a test of their ideologies. It would prove to be a synecdoche of the entire Cold War between the capitalist United States and the socialist Soviet Union.

The starting pistol in the race to the future was fired in 1961 when President John F Kennedy committed to “achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth” and it ended with a US victory on 24 July 1969 when the crew of the Apollo 11 mission splashed down safely in the Pacific Ocean.

There are no such stakes in today’s race. The values of the future aren’t in question, merely the egos of three billionaires. One of these men is launching his private spacecraft off the planet on Sunday. Another follows suit soon after.

So here’s how they compare and what you need to know:

“My mum taught me to never give up and to reach for the stars,” said Sir Richard Branson announcing that he was going to be among the first people his spaceflight company launches on a mission.

Unfortunately, not only will Virgin Galactic’s mission fall short of the stars, the two-and-a-half hour mission will also fall short of space, at least according to the internationally agreed definition.

VSS Unity is a spaceplane (perhaps just a plane?) that launches in mid-air from the belly of a carrier aircraft at an altitude of about 15km, and then flies up to an altitude of about 80km, allowing the passengers to feel nearly weightless for approximately six minutes and glimpse the curvature of the Earth.

The problem for Sir Richard is that the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) defines the boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space as 100km above Earth’s mean sea level, the so-called Karman Line, 20km higher than he is going to travel.

The definition of the edge of space is a bit of a challenge. Earth’s atmosphere doesn’t suddenly end but becomes progressively thinner at greater altitudes. In very simple terms, physicist Theodore von Karman’s solution was to define the edge of space as the highest point at which an aircraft could fly without reaching orbital velocity.

While Karman himself and the FAI regards this altitude as 100km, Sir Richard has the US Air Force and NASA on his side. They both place the boundary of space at 80km above mean sea level, partially because putting it at 100km would complicate issues regarding surveillance aircraft and reconnaissance satellites for the US – although the Department of Defence subscribes to the FAI definition.

It’s not clear whether this definition is covered by the small print of Virgin Galactic’s customer tickets, but ultimately the company aims to be operating multiple space tourism flights a year, and already has more than 600 customers for the $250,000 (£189,000) seats – including Justin Bieber and Leonardo DiCaprio.

“Ever since I was five years old, I’ve dreamed of traveling to space. On 20 July, I will take that journey with my brother,” said Jeff Bezos, announcing his seat on a journey to the edge of space.

Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket is capable of actually making it there, with a maximum achieved altitude of above 100km, but how high it will bring its four passengers hasn’t yet been confirmed.

These passengers will be Jeff Bezos, his brother Mark, a mystery customer who paid $28m (£20m) for the seat in an auction, and 82-year-old Mary Wallace “Wally” Funk, a woman who had astronaut training in the 1960s but was denied the chance to go into space because of her gender.

While the mission will be scooped to launch by Virgin Galactic, by inviting Wally Funk it has managed to scoop Branson on getting a famous victim of gender injustice into space – she had previously put money down to fly with Virgin Galactic.

It will take three minutes to take the passengers up to the required altitude, at which point they will have three minutes more in which to enjoy their sudden near-weightlessness. They’ll be allowed to unbuckle their seatbelts and float around, as well as examine the curvature of the Earth through one of the capsule’s windows. Just over 10 minutes after launch, the spacecraft will land back on Earth.

The 20 July flight will fittingly occur on the anniversary of the moon landings in 1969, but unlike the Apollo missions there will be no human piloting the modules. Instead, Blue Origin’s New Shepard spacecraft is completely autonomous and will follow a programmed mission timeline before parachuting back to Earth.

The company has said that it expects to sell seats for more tourism flights in the future, but it isn’t clear how this will happen and the tickets for New Shepard are yet to go on general sale.

“I want to die on Mars – just not on impact,” Elon Musk once quipped, although he hasn’t announced his immediate intention to travel into space at all.

Unlike both Bezos and Branson, Musk’s private spaceflight company, SpaceX, has a long and successful history of launching payloads way beyond the 100km mark.

SpaceX has announced it will be launching an all-civilian mission into orbit by the end of the year, with the passengers actually orbiting around the planet for up to four days before returning to Earth.

All four crew seats on the mission have been paid for by Jared Isaacman, the founder of Shift4 Payments, who has declined to reveal the costs.

Isaacman is donating two of the seats to St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, with one being given to a staff member there, and another intended to be raffled off to a member of the public. He hopes to raise $200m (£145m) for the hospital, alongside a $100m (£72m) donation of his own.

Elon Musk hasn’t mentioned flying on this mission himself, although he has long articulated a plan to travel to Mars, plans that have been described as a dangerous delusion by Britain’s chief astrophysicist Lord Martin Rees.

Back in 2016, Musk outlined his vision of building a colony on Mars “in our lifetimes” – with the first rocket propelling humans to the Red Planet by 2025.

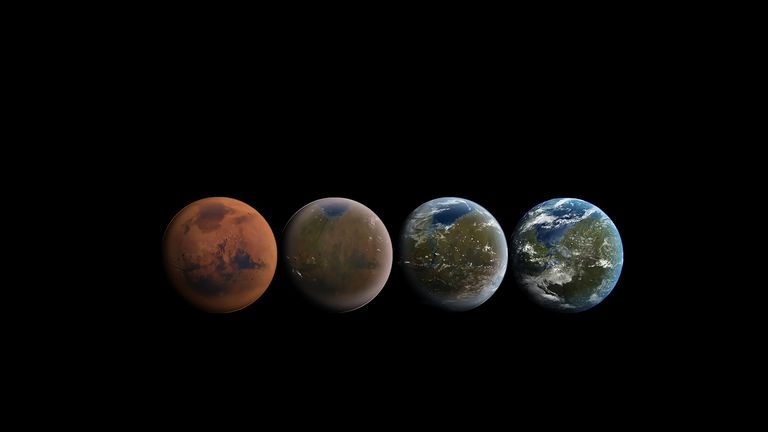

For many years the company used an image of the Martian surface being terraformed (turned Earth-like) in its promotional material. However, a NASA-sponsored study published in 2018 dismissed these plans as impossible with today’s technology.

Recently Musk has tweeted he believed it was “possible to make a self-sustaining city on Mars by 2050, if we start in five years” but as of yet, SpaceX has not planned any missions to the planet.