Over the next two weeks, three space missions will reach Mars, one orbiter and two landers, after spending seven months in space.

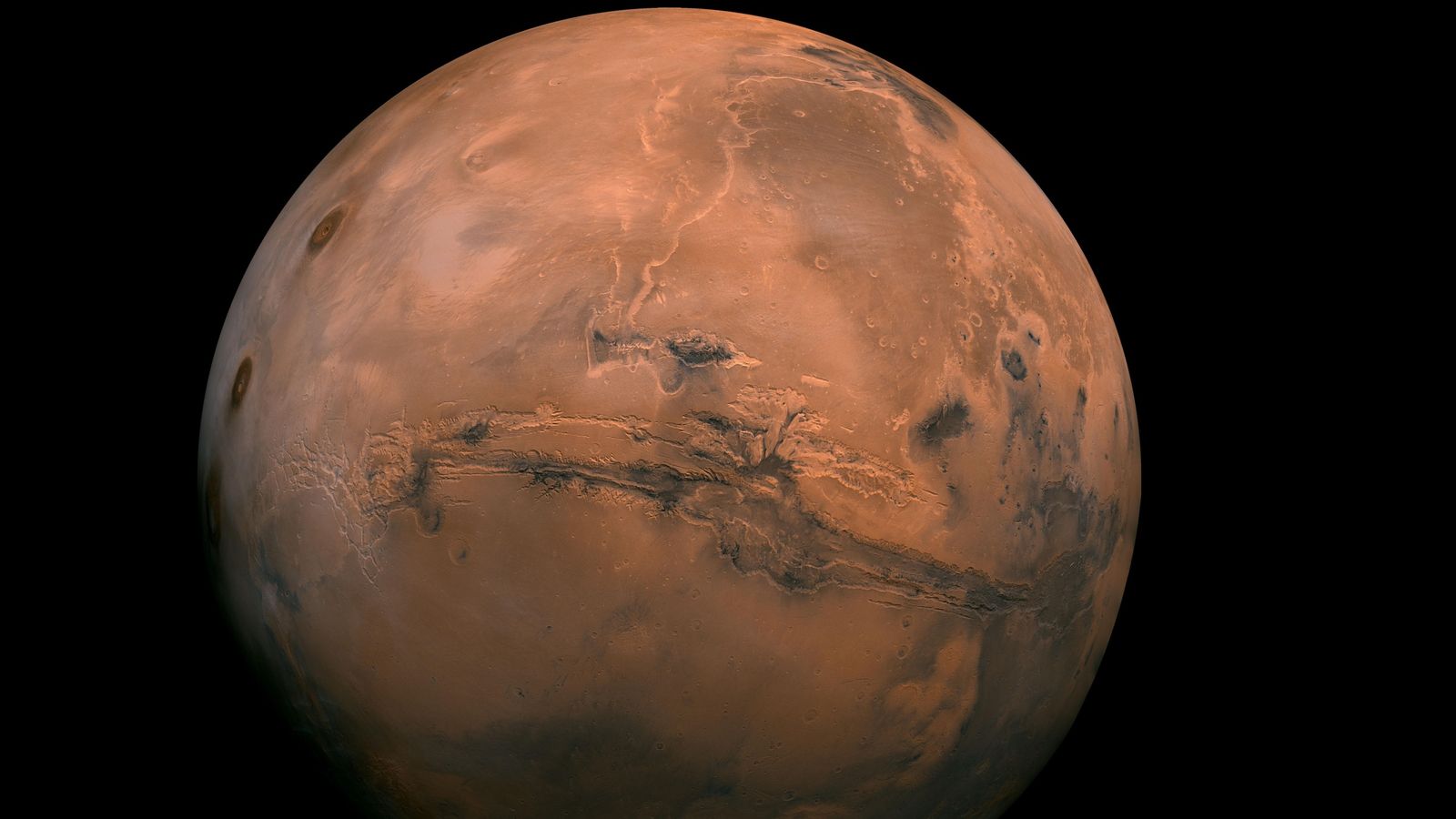

The three missions launched in July 2020 forming a wave of unmanned spacecraft from United States, China and the United Arab Emirates to see if Mars was ever habitable, and to find out if it could be again.

The timing of the launches was dictated by Mars and Earth’s orbits, with a single one-month window during which the planets are close enough together to permit the seven-month journey. That window wouldn’t have opened again for another 26 months.

Here are the dates to stick in your diary and an explanation of what we can expect.

9 February, the United Arab Emirates’s Amal probe

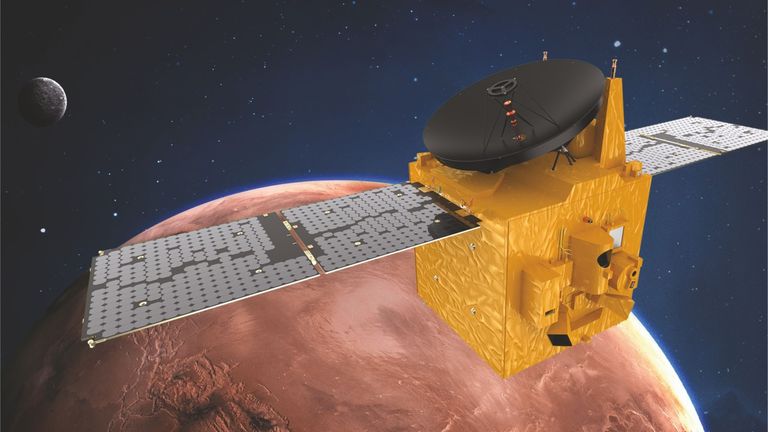

The United Arab Emirates launched its first mission to Mars from Japan’s Tanegashima Space Centre on 19 July 2020. Of the three missions, it is perhaps the least risky – but it will also be the first to commence.

The £160m satellite aims to provide a picture of the Martian atmosphere and study daily and seasonal changes on the planet, as well advancing the UAE’s science and technology sector, enabling it to move away from its economic reliance on oil.

The Emirates Mars Mission (EMM) will see the Amal (Hope) probe inserted into orbit around the planet on 9 February, when it will start sending data back to Earth, with a delay of between 13 and 26 minutes.

Scientists believe Mars was once abundant with water, and very possibly life. The UAE Space Agency said: “One of the culprits of the transformation of this planet into a dry, dusty one is climate change and atmospheric loss.”

The agency’s probe will monitor the Martian weather system, as well as the distribution of hydrogen and oxygen in the upper portions of Mars’ atmosphere – enabling humanity to understand the link between weather change and atmospheric loss.

“Using three scientific instruments on board of the spacecraft, EMM will provide a set of measurements fundamental to an improved understanding of circulation and weather in the Martian lower and middle atmosphere,” according to the Emirati space agency.

“Combining such data with the monitoring of the upper layers of the atmosphere, EMM measurements will reveal the mechanisms behind the upward transport of energy and particles, and the subsequent escape of atmospheric particles from the gravity of Mars.”

10 February, China’s Tianwen-1 mission

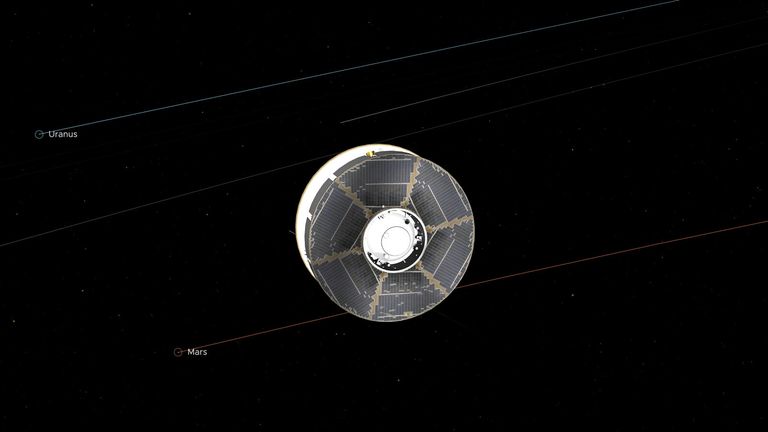

China joined the search for signs of life on the red planet by launching its own Mars rover into space on 23 July 2020.

Tianwen-1, which means “quest for heavenly truth”, took off from Hainan Island off the south coast of China with hundreds of onlookers watching from a nearby beach.

Its orbital insertion is planned for 10 February, although the lander won’t attempt to reach solid Martian ground until May. Once there it plans to search for underground water and evidence of possible ancient life forms.

China National Space Administration is, like most government departments in China, much less public and transparent about its work than NASA, and it isn’t clear how much information about the mission will be made public.

The tandem spacecraft – with both an orbiter and a lander containing the rover – is expected to enter Mars’ orbit in February and is aiming to touch down on a landing site on Utopia Planitia.

NASA detected possible signs of ice at the site, according to an article in Nature Astronomy by mission chief engineer Wan Weixing, who died in May last year after battling cancer.

The 240kg solar-powered device will operate for around three months when it touches down on Mars and will sniff around for biomolecules and biosignatures in the soil, while the orbiter is due to last two years.

The launch is China’s second attempt at heading to Mars.

Only the US has successfully landed a spacecraft on Mars, doing it eight times since 1976.

More than half of the spacecraft sent there have either blown up, burned up or crashed into the surface, including China’s last attempt – in collaboration with Russia – in 2011.

18 February, NASA’s Perseverance rover

NASA’s Mars 2020 mission launched from Cape Canaveral in Florida on 30 July 2020, and after seven months in space is set to explore the Martian environment for signs of its past habitability as well as signs of life.

The mission is set to land on Mars in the early afternoon of 18 February 2021, there will not be much time for deliberation when it is heading towards the Martian surface.

Excitingly the mission carries more cameras with it than any other interplanetary mission in history, according to NASA.

The rover itself has 19 cameras which will send back breathtaking images of the Martian landscape, while four other cameras are attached to the parts of the spacecraft involved in entry, descent and landing.

These will allow engineers to put together a high-definition view of the landing process, as well as allow people at home to follow along with raw and processed images.

The rover, which has a mass of 1,050kg (2,313lbs), could easily simply add to the craters on the planet’s surface.

NASA hopes its brand new guidance and parachute-triggering technology will help steer the rover away from these hazards but its controllers back on Earth will be helpless.

Radio transmissions from Mars take 10 minutes to reach Earth so by the time the controllers see Perseverance has entered the atmosphere, it will have either already landed or been destroyed.

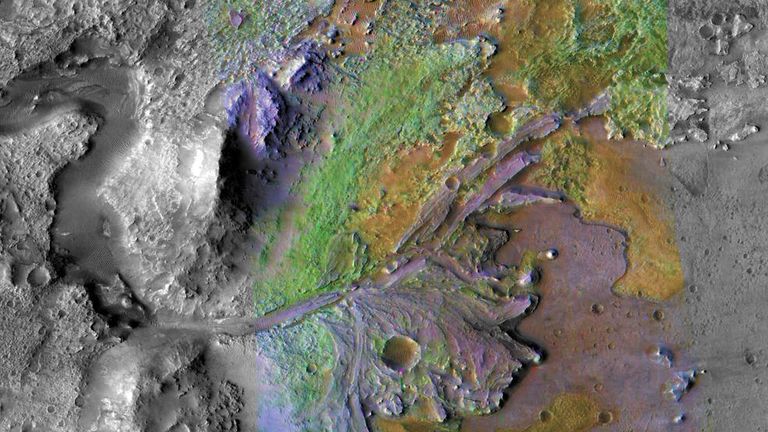

The Perseverance rover is intended to touch down in an ancient river delta and former lake on the Martian surface known as the Jezero Crater.

The Jezero Crater is full of obstacles and dangers to the rover, including boulders, cliffs, sand dunes and depressions, any one of which could end the mission, both in landing and as the rover drives along the surface.

The deposits in the crater are rich in clay minerals, which form in the presence of water, meaning life may have once existed there – and such sediments on Earth have been known to store microscopic fossils.

Scientists have also noted that the crater doesn’t have a depth which matches its diameter, which means sediment likely entered the crater through flowing water – potentially up to a kilometre of it.

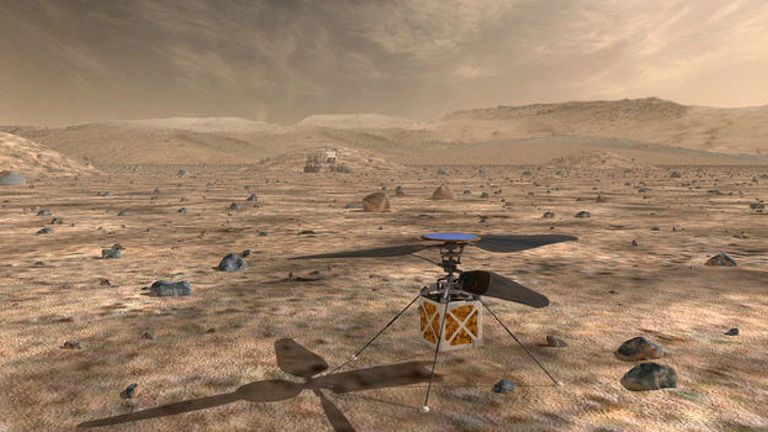

Perseverance is also equipped with a miniature helicopter named Ingenuity which weighs just 4lb (1.8kg) and will be the first rotorcraft to fly on another planet.

“The laws of physics may say it’s near impossible to fly on Mars, but actually flying a heavier-than-air vehicle on the red planet is much harder than that,” the space agency quipped.

The little chopper underwent a series of drills simulating the mission in a testing facility in California, including a high-vibration environment to mimic how it will hold up under the launch and landing conditions, and extreme temperature swings such as those experienced on Mars.

The autonomous test helicopter will have an on-board camera and will be powered by a solar panel, but will not contain any scientific instruments.

NASA aims to develop the drone as a prototype to see if it could be worth attaching scientific sensors to similar devices in future.