In Washington circles and beyond, officials bristle at suggestions that the decision to supply cluster munitions to Ukraine represents an erosion of the moral high ground for America or that it suggests the war isn’t going well for Ukraine.

On the first point, Congressman Adam Smith, a ranking member of the Senate’s Armed Services Committee, told me: “Well, forgive me for being so blunt about this, but no, it does not erode the moral high ground. The only way it erodes the moral high ground is if either you’re an idiot, or you’re rooting for Russia in this conflict.”

The congressman, a Democrat, who was until January the chair of the Armed Services Committee, said: “When you look at what Russia is doing in Ukraine, when you look at the way they are still indiscriminately bombing civilian populations, knocking out hospitals and schools and shopping malls and apartment buildings all across the country, without a single military objective in mind, spraying ordnance all across the country, killing people, torturing people. What Ukraine is doing is trying to retake their country and no weapon of war is peaceful.”

On the second point, that the decision to send cluster munitions is a signal that the war is not going well, the argument is more nuanced.

The blunt reality is that the Ukrainian counteroffensive is not having the success which had been hoped. They are getting through alarmingly large quantities of ammunition. Stocks are critically low – President Biden was remarkably candid about this.

That is not to say that the Russians have the upper hand or are somehow doing better than the Ukrainians. But they are dug in and hard to budge. Putin also has the luxuries of time and personnel. It’s true to say that neither side can claim battlefield success right now.

That’s why America is arguing that cluster munitions of a particular type – fired from artillery pieces rather than being dropped from planes – must now be deployed. They bridge a supply problem, and they can significantly change Ukrainian fortunes on the battlefields.

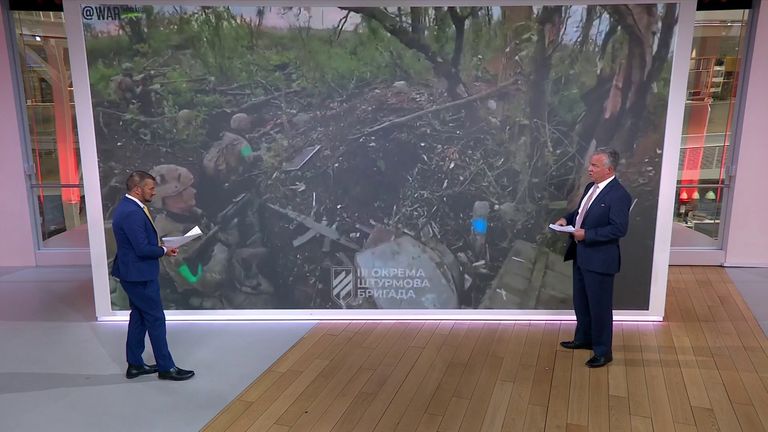

The Biden administration is holding Ukraine to a pledge not to use these weapons on civilian targets or areas. Ukraine says it will use them on the eastern battlefields to take out dug in Russian forces.

They will have a material impact. When the Americans used cluster munitions on the Iraqi forces in 1991, Iraqi commanders described the incoming weapons as “steel rain”.

The Americans also claim that the “dud rate” of their DPICM (dual-purpose improvised conventional munition) is +/-2%. That means that only about 2% of the “bomblets” distributed over an already ordinance-strewn battlefield will fail to explode.

Read more:

NATO head ‘absolutely’ confident allies will agree on formal wording about Ukraine’s alliance membership

Rishi Sunak ‘discourages’ use of cluster bombs after Biden agrees to send controversial munitions to Ukraine

President Biden agrees to send controversial cluster munitions to Ukraine

If you are firing hundreds of shells each of which contain many more bomblets, 2% isn’t insignificant.

But, it does compare favourably to the +/-30% dud rate of NATO cluster munitions used in the Yugoslav War of the 1990s or for that matter to the dud rate of the cluster bombs Russia is using right now on civilian targets in Ukraine.

The statements of unease about the US decision from other NATO countries are predictable.

They are bound by the 2008 convention banning the use of all cluster munitions. The subtext of the statements by the UK, Germany, Canada, New Zealand and others is, effectively, “we’d rather they were not on the battlefield, but we recognise their necessity, we note their low dud rate, and we need to see Putin fail”.

So watch for discussion about cluster munitions at the NATO summit but don’t expect it to overshadow the meeting. NATO unity is key.

A bigger threat to that unity could come from substantive discussions on Sweden’s accession to the alliance. Turkey has objections, as does Hungary. Sources say these objections can be overcome soon.

The other key topic will be the prospect of Ukraine joining NATO. This won’t happen until the war is over.

Beyond the fact that Ukraine hasn’t yet completed the necessary security and democratic reforms necessary for NATO membership, there is a more practical issue.

If Ukraine was to be granted membership now then NATO’s Article 5 (an attack on one member is an attack on all) would be automatically triggered because Russia is actively attacking Ukraine. That would compel NATO forces to attack Russia.

But, a carefully worded conditional commitment on Ukrainian membership to NATO when the war is over is likely soon. In the shorter term look out for other security commitments now.